Andreas Schlüter the Younger (b. 1659/60, d. 1714)

Schlüter was born most likely in 1659 or 1660 in Gdańsk, the son of a local carpenter and member of the woodworkers’ guild, Andreas Schlüter the Elder, and Catherina; the sculptor Ernst Schlüter (d. 1700), who worked in Berlin, was most likely his brother. Andreas the Younger had four children with his wife Anna Elisabeth Spangenberg, of which only his eldest son David (b. 1693, d. after 1717) chose to become an engineer and architect. Andreas the Younger’s incomparable talent and comprehensive abilities as a sculptor and architect were appreciated, in turn, at the royal courts of Jan III in Warsaw (1688/9–1694), Elector (King) Friedrich III (I) von Hohenzollern in Berlin (1694–1713), and Tsar Pyotr I the Great in Russia (1713–4). He died in 1714 in Moscow, having left St. Petersburg when his designs, town plans, and architectural projects, prepared for implementation in the new capital of Russia, were stolen. Schlüter is commonly touted as the most distinguished author of High Baroque sculpture in Central Europe, and since 1861 his only partly documented oeuvre has sparked numerous analyses from an array of scholars from Germany (Cornelius Gurlitt, Heinz Ladendorf, Wilhelm Boeck, Alfred Schellenberg, Jörg Rasmussen, and Guido Hinterkeuser), Poland (Tadeusz Mańkowski, Mariusz Karpowicz, Wojciech Fijałkowski and Henryk Kondziela, Stanisław Mossakowski, and Zygmunt Iwicki), and the United States (Kevin E. Kandt).

The time and circumstances of Schlüter’s education as an artist remain largely unknown, with earlier studies debating two main hypotheses indicating France and Italy as two alternative locations of Schlüter’s professional initiation. A more recent theory suggests that he may have stayed in Holland and the Spanish Netherlands for a considerable period of time. Little is also known of the beginnings of Schlüter’s individual activities following his return to Gdańsk, and the commonly accepted catalogue of works attributed to the artist needs to be verified in the light of the latest archival research and interpretations of historical material.

Past monographers of Andreas Schlüter the Younger had thoroughly embraced Kondziela’s claim that the artist was responsible for details of ornamental decoration made in Gottland’s Burgsvik sandstone found in the façade of the Royal Chapel in Gdańsk (founded by King Jan III), dating the work to 1680–1. One should nonetheless consider the temporal incongruity between the time of creation of the decorations in the chapel and Schlüter’s biography. If the claim of his birth in 1659 or 1660 is to stand, then Schlüter must have worked on the façade at 20 or 21. At that age, members of the sculptors’ guild — to which Schlüter, a native of Gdańsk, a typical Hanseatic city with strict artisanal regulations, must have belonged — were usually expected to serve an apprenticeship or spend the final stage of their development practising under master craftsmen in the latter’s workshops. Individual work, of which this royal project is an obvious example, was usually the sole province of masters-entrepreneurs.

The luxuriant and realistic ornaments in the chapel replicate the customary set of forms of architectural embellishment which were en vogue in the Netherlands at the time, being derived directly from nearly identical details in the exquisite interiors of the Amsterdam town hall (1650–3, designed by Jacob van Campen, made by Artus Quellinus the Elder with workshop), popularised across Europe thanks to a series of etchings by Hubertus Quellinus, published by Frederick de Witt in a collection entitled Voornaamste Statuen ende Ciraten van het konstrijk Stadthuys van Amsterdam… (Latin title: Prima pars Praecipuarum effigierum ac ornamentum amplissimae curiae Amstelodamensis…). However, the sculptural details in the Royal Chapel do not bear the classic features of Schlüter’s classicising style. They are too heavy and naturalistic, and include shoots of dried acanthus — an ornament of south German origin, which appears only rarely and sparingly in the artist’s other works. The formidably carved heads of angels flanking the main portal — which survived World War II — with their sharp facial features, painstakingly detailed eyes and lush hair, do not resemble the thus far acknowledged figural works by Schlüter in any way. The indubitable attribution of the decorations at the Gdańsk chapel to Schlüter rested on an argument based on a misinterpretation of a fragment from a letter sent from Wilanów by Agostino Locci the Younger to the King on 31 October 1681, published by Starzyński in 1933. In the letter, the architect praised an unnamed sculptor — author of a bozzetto or modello of the ‘Fiamingo children’. The sculptor in question was supposed to have previously worked for the monarch in Jaworów. Eventually, Mańkowski identified him with the young artist from Gdańsk, possibly on the basis of Gurlitt’s loose observations concerning Schlüter’s supposed involvement in the making of stucco decorations at Wilanów. These considerations were expanded and verified for posterity by Kondziela. The claim of Schlüter’s employment in Wilanów and Warsaw already in 1681, that is, immediately after the completion of works in Gdańsk, contradicts not only the aforementioned information about the selfsame statuarius staying in the King’s private estate in the Rus’, but even the very fact of Schlüter’s involvement in making two sepulchral monuments made from materials available in Gdańsk — Burgsvik sandstone from Gottland (the same kind that was used in the Royal Chapel) and Noir Belge / Noir de Namur limestone from the Meuse region — of Canon Joachim Pastorius von Hirteberg (d. 1681) and Adam Zygmunt Konarski (d. 1685) in the Frombork cathedral (ca. 1682 and 1685–7, respectively), as well as the main altar, in stone, alabaster, and stucco, along with a cartouche and putti in the main portal of the Cistercian church in Oliwa, which are convincingly attributed to Schlüter.

A clue suggesting the identity of the author of the decorations on the façade of the Royal Chapel is provided in Kandt’s mention about the employment of Johann Rohde a.k.a. Rohden — a German sculptor familiar with Italian art and tied to Jan III and Treasurer of the Crown Jan Andrzej Morsztyn — in its making. Another clue can be derived from a comparative analysis of the decoration at the slopes of the drum of the chapel’s central dome, which consist in leafed masks with a broad shell in place of the lower clamp, with the highly similar alabaster grotesques adorning the door-frame of the chapel of Our Lady of Chęstochowa in the ambulatory of Gniezno cathedral, carved in 1690–1 by Hans Casper Äschmann, a stonemason from Hamburg, who was an elder in the guild of builders, stonemasons and sculptors. The form of the consoles and the alabaster statues of unidentified martyr saints and angels, which decorate this portal, are almost identical to figures in the sandstone portal at the house at 25 Ogarna Street in Gdańsk (ca. 1680, mistakenly attributed to Schlüter), indicating a certain general influence of the figural representations by Hans Michael Gockheller, as Pałubicki convincingly demonstrates.

The newly-instituted division — motivated by archival findings — between works of Schlüter and those of Andreas Schwaner at Warsaw and Wilanów allowed for the period of Schlüter’s stay in the capital of the Commonwealth to be established at 1688–93/4, a contention supported by the extant record of christenings of two of the artist’s children: Hedwig Elisabeth and David. The period abounded in prestigious assignments from outside of the royal court, commissioned by two most prominent patrons of that period: the Voivode of Płock Jan Dobrogost Krasiński and the Grand Marshal of the Crown Stanisław Herakliusz Lubomirski. For the former, Schlüter prepared two figural scenes in relief in Szydłowiec sandstone under the guidance of Tielman van Gameren — The Duel of Marcus Valerius Messala Corvinus with a Gaul and The Triumph of Marcus Valerius Messala Corvinus in Rome, placed within the two tympanums — and a cartouche with Krasiński’s coat of arms for his palace at Miodowa Street (made in collaboration with Beniamin and Ferdinand, two assistants brought over from Gdańsk), as well as a wooden crucifix masterfully depicting the death of Christ, later placed in the church of Reformed Franciscans in Węgrów. The latter patron presented Schlüter with Tielman van Gameren’s designs for a Bernini-inspired, pyramid-shaped, carved altarpiece — the Confession of St. Boniface, intended for the Bernardine church at Czerniaków which Lubomirski funded (1692–3). For this temple, Schlüter produced the carved figural elements of three altars, derived directly from the famous Roman putti fiamminghi devised by François Duquesnoy. The complex of works completed in that period culminates in a wooden crucifix for the side altar of the Franciscan temple in the New Town district of Warsaw. These works are marked by a thorough reliance on modern tendencies in sculpture in the Netherlands (Pieter t’Hooft in the Hague, Bartholomeus Eggers in Amsterdam, and Pieter Rijx in Rotterdam) and Flanders (Artus Quellinus the Elder and Pieter Verbrugghen the Elder in Antwerp and Jean de Cour in Liège), which Schlüter acquainted himself with most likely during his travels as an apprentice or educational visits in the late 1670s and early 1680s. On the other hand, no source or convincing artistic argumentation exists that would support the hypothesis of Schlüter’s involvement as a sculptor or designer in Wilanów itself — the post of Jan III’s favourite sculptor was at that time occupied by the comprehensively talented Stephan Schwaner (mentioned in records for the years 1681–92).

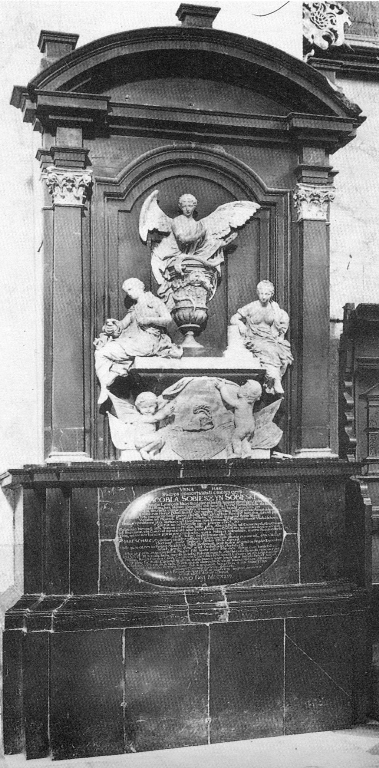

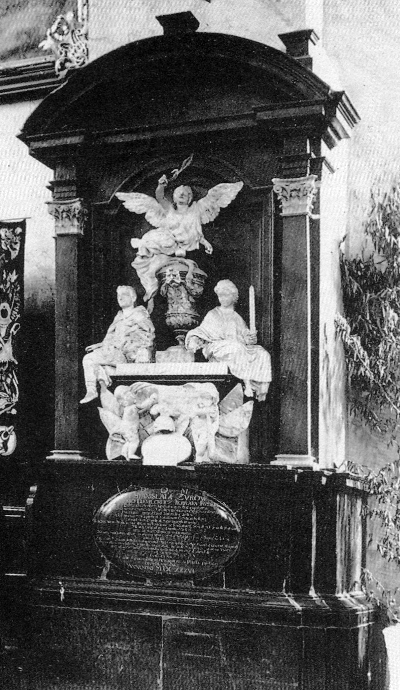

Locci’s other letters published by Mańkowski prove that in 1692–4 the city over the Motława river became the setting for the creation of sculptural elements in alabaster for two pairs of gravestones, designed by the Italian under a commission from the King and intended for installation at Zhovkva. They arrived to Zhovkva by way of Warsaw and Wilanów on rafts, together with bronze cannon barrels cast in the Gdańsk foundries. Archival record do not support the idea of any relation these works would have to Warsaw or Wilanów. The monuments, a part of the mausoleum to the fame and glory of Hetmans and warriors of the family of Stanisław Żółkiewski (d. 1620), were dedicated to the father and uncle of the King — Jakub Sobieski (d. 1646) and Stanisław Daniłowicz (d. 1636), placed in the collegiate church (deeply damaged after 1945) — as well as his mother Zofia Teofila (d. 1661) and brother Marek (d. 1652), in the Dominican temple (destroyed in a fire in 1739 or 1754, replaced with stucco figures in the style of Lviv Rococo). One should note that the two pairs of monuments, slightly distinguished by the shape of the articulation of the black marble structures shaped as simple aedicula enclosed in a segmental pediment, were ordered in 1686 at a stonemason’s in Dębnik near Cracow from stonemasons Jacek Zagórski and Błażej Mizerski, associates of master Michał Poman. The design may be attributed to Locci himself. Authors of monographic works devoted to the gravestones — Mańkowski and Kandt — have conducted an in-depth analysis of their erudite iconographic and conceptual programme, whose most significant elements are the figures of cardinal virtues, genii, and a pair of putti dressed in the garb — or bearing attributes — of ancient deities and heroes (Minerva/Pallas Athena and Hercules), which surround the classicising, figural urns bearing the ashes of the deceased, adorned with figural reliefs. The thoroughly classicised figures dressed in ancient garb were marked by an uncommon attention to detail, made possible by a material which gave the artist unlimited possibilities of perfecting the shape of the carvings. Both aforementioned authors also presented numerous indications of the sources of the repertoire of formal and stylistic devices employed in the works, including mostly Flemish and Dutch works of the second half of the seventeenth century, such as the emblematic and allegorical engravings on the theme of vanity, made by Otto van Veen.

At this point, one might recount another instance of reception of a specific Roman motif invented by Duquesnoy — the pairs of cherubs pulling at the drapery covering the figural composition, found at the bottom of both works. Their original source was Ferdinand van der Eynden’s famous epitaph at the church of Santa Maria dell’Anima in Rome (1633/5–40), and the motif was popularised in the Netherlands in the latter half of the 1650s by the most distinguished student of Artus Quellinus the Elder, Rombout Verhulst. Schlüter interpreted the already common device of the Flemish artist in a much more innovative manner. The composition of an antithetically posed pair of putti, turned toward the viewer with hands above their heads — the one on the left on the gravestone of Stanisław Daniłowicz, the one on the right on the monument of Jakub Sobieski — immediately recalls one of Duquesnoy’s compositions. By lending attributes of Hercules — the lion’s skin it wears and the club it leans on — to the right-handed putto on Stanisław Daniłowicz’s monument, Schlüter could compile elements of a pair of analogical figures in the epitaphs of the family of Frederick Rissen (in the Calvinist church in Purmerend, Netherlands) and an unidentified person in the Schleswig cathedral, both made around 1660 by Bartholomeus Eggers of Amsterdam. The figural groups in the gravestones at Zhovkva constitute the most accomplished examples of the Flemish tendency in sculpture of the late seventeenth century in the Commonwealth. The question of the reception of Schlüter’s style and his works in Warsaw and the entire Commonwealth has not yet been sufficiently researched.

The absence of an anticipated promotion at the royal court or further serious commissions in Warsaw prompted Schlüter to depart for Berlin, where he arrived no later than in the mid-1694 at the behest of Eberhard von Danckelman, Chairman of the Royal Council and Prime Minister of Brandenburg, then-current favourite of Prince-Elector Friedrich III von Hohenzollern (who became King in 1701 as Friedrich I of Prussia). Schlüter’s activity during this period is the most documented and comprehensively researched part of his career, abundant in works in sculpture and architecture of a European calibre. Since 1695, he was involved in the formation of the new Academy of Fine Arts, which he directed between 1702 and 1704 (in 1695–6, he received court scholarships for trips to France and Italy, which allowed him to witness sculptures at Versailles and in Roman circles of Algardi and Bernini, combining classicising figural sculptures with a profusion of progressive High Baroque architectural and ornamental forms). In recognition of his achievements as builder and engineer, he was inducted to the Academy of Sciences in 1701–10, and knighted in 1705. Schlüter became the first sculptor and royal designer to receive a majority of the most prestigious commissions from the monarch: three official bronze statues of the Elector at the Long Bridge in Berlin and in Königsberg (1696–1703 and 1696–7), the erection of the Arsenal with the famous sculptural decoration including 22 masks of dying warriors (1696 and 1698–9), a new architectural framing and interiors of the grand Castle (1698–1707), the Old Post Office (1701–4), and Mint (1698–1708). He was also employed by a select group of influential depositories of power at the court in Berlin and in Stralsund, becoming a major figure in the world of arts in Brandenburg and Prussia, and by extension in entire Central Europe, at the time. In 1707, on the back of a few building disasters and feuds with the local officials and artists, he fell out of favour, and his output was limited exclusively to sculptures, such as the bronze sarcophagi for the royal couple in the Berlin cathedral (after 1705–13). In his Berlin period, Schlüter educated several pupils: the architects Martin Böhme (1676–1725) and Paul Decker (1677–1713), and sculptor Johann Georg Glume (1679–1765). They continued a string of Schlüter’s projects — for instance, equipping the Berlin castle — but never attained the level of ability of their master. The worsening financial situation of the artist’s family forced him to move first from Berlin to Freienwalde, and then, in 1713, to take up work in Saint Petersburg for Tsar Pyotr I the Great, where he put forward visionary town plans for the new capital of Russia and Baroque designs of the most important residential structures, such as the Tsar’s Summer and Winter Palaces, the main body of the Peterhof, the Favorit villa in Oranienbaum, and palaces for a few aristocrats. These buildings were subsequently rebuilt in eighteenth and nineteenth century. Schlüter’s stay in Russia ended abruptly with the premature death of the artist.

Translation: Antoni Górny

We would like to inform that for the purpose of optimisation of content available on our website and its customisation according to your needs, we use information stored by means of cookies on the Users' end devices. You can control cookies by means of your Internet browser settings. Further use of our website without change of the browser settings means that you accept the use of cookies. For more information on cookies used by us and to feel comfortable about this subject, please familiarise yourselves with our Privacy Policy.

✓ I understand