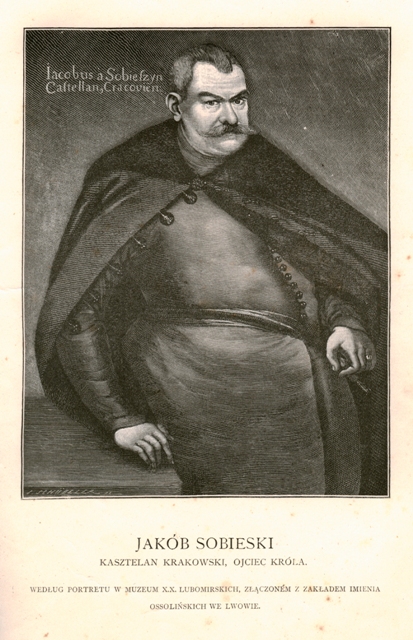

The similarity of the education of a young Roman and a young Polish magnate who, in accordance with the convictions prevailing in Poland at the time regarded himself as an heir of Roman tradition, is of considerable significance. In a textbook comparable to a contemporary encyclopaedia, full of directives referring to assorted domains of knowledge (rhetoric, law, politics, agriculture, the art of war) Cato the Older advised his son, Marcus, about the principles of life, stressing that education embraces two realms of life: intellectual and ethical. Hence Cato’s famous definitions: Orator est vir bonus dicendi peritus, Agricola est vir bonus arandi peritu. In his treatise De Officiis, Cicero, Cato’s junior, pondered on practical morality and offered guidance to his son concerning the duties of man and citizen. In turn, Jakub Sobieski, an expert on, and eager reader of, ancient authors, carefully created, in the manner of a true pater familias, an educational programme for his sons, Marek and Jan, and obligated the carefully chosen tutors not only to observe the principles that he had devised, but also to make a detailed account of their implementation. The directives formulated by Sobieski declared that education should prepare a young man to play the role of a farmer, a citizen and a politician, and ought to be closely connected with moulding his character and developing virtues. Hence the educational instruction contains counsel concerning travelling and teaching foreign languages. “The primarius outcome of inter alios benefits of peregrinations is to learn foreign languages. To know languages is the ornament of every Polish nobleman and primary among all virtues. This holds true not only for the Polish nobleman but for every homo politicus: his skill will prove useful at the court and in Republica for assorted legations and services rendered to the King and Commonwealth”. Today, it appears that the father of the young Sobieskis represented an extremely modern approach to education and knew from his own experience that travelling and learning foreign languages are indispensable for educating a young man.

Learning foreign languages – paternal plans foresaw several hours daily – created the danger of deforming the native tongue. Upon several occasions, Sobieski stressed that he wished his sons to be fluent not only in Latin. They should be well acquainted also with the vernacular and customs: ”In Poland people correctly jeer those who are wise in Latin but fools in Polish (…)”, ”When they attend a banquet, or a meeting held in the company of the ladies, they may dance to their hearts’ desire, and I do not want them to be only wise in Latin but to be polite also in Polish. After all, they are not to be trained to don a priest’s frock”. Concern for fluency in foreign languages and the native tongue went hand in hand with attention drawn to winning social graces. Conversation, dances, fun, social meetings, receptions – as long as they are civilized – all are worthy of a young man.

The educational instruction of Jakub Sobieski included also counsel referring to daily obligations, life style and physical exercises. The attentive father took good care of daily life as a whole: food – “I would like the stomachs of my sons to become used to rough victuals which, God willing, they shall eat while at war...”; clothes - ”so that while in the capital they do not wear torn or mended garments”, and mutual relations between the brothers, who were taught together: ”Mr. Orchowski must observe predominantly that the brothers love each other, with no jealousy or offences. May the younger respect the older and the older love the younger”.

The guardians–preceptors of the young Sobieskis were obligated to present detailed accounts of the progress made by Marek and Jan. The young men maintained a steady correspondence with their father, describing events at schools and their journeys. Apparently, the instruction issued by Sobieski contained not only directives concerning the contents of the instruction and upbringing; as an experienced pedagogue, he also outlined the methods to be applied by the two sons while acquiring knowledge. The rules on learning while travelling appear it be particularly interesting: ”Whenever you travel, tour the large towns, ask about their owners and who rules them, what sort of garrisons are stationed there, take a look at the location and note everything down in your book”, or the recommendation to study foreign languages and to avoid establishing closer acquaintances with foreigners so as to avoid trouble: “Until you perfect your knowledge of language, I urge you not to seek the company of courtiers since the French are a frivolous and unreliable nation”.

The schooling programme also contained injunctions concerning physical exercises and religious practices, comments on behaviour in lodgings and assorted rules concerning orderly conduct. Apparently, there was not a single domain of life, which the cautious father did not include in his educational curriculum. Envisaging his sons as future commanders and diplomats he clearly defined the objective of schooling in a letter addressed to one of them: ”I wish to prepare you not for a calm or detached existence (...) but for public life or the hardships of the war camp”.

We would like to inform that for the purpose of optimisation of content available on our website and its customisation according to your needs, we use information stored by means of cookies on the Users' end devices. You can control cookies by means of your Internet browser settings. Further use of our website without change of the browser settings means that you accept the use of cookies. For more information on cookies used by us and to feel comfortable about this subject, please familiarise yourselves with our Privacy Policy.

✓ I understand