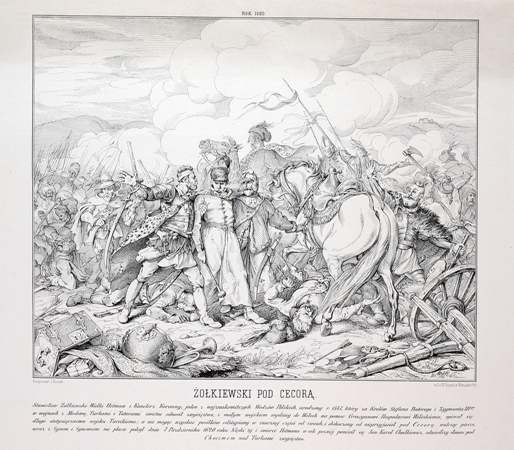

The Cecora defeat of 1620 when the Turkish-Tatar forces crushed the troops under Hetman Stanisław Żółkiewski withdrawing from Moldova seemed to promise an easy victory for the Turks. The very young Sultan Osman II held sway over the Ottoman Empire, dreaming of conquests as great as those of his 16th century ancestor, Suleiman the Magnificent who made the then Europe tremble with fear. Osman quickly organized the Khotyn expedition, however, not very successfully estimating the military capabilities of both his own army and the opponents. The Polish-Lithuanian forces and the allied Cossacks successfully resisted consecutive attacks. The Ottoman soldiers could not cope with the rainy autumn. The Sultan’s advisors, reluctant to war, urged him to call a truce, assuring him about the Poles’ tendency to make concessions and even to pay tribute. Finally, the ruler was persuaded to retreat. Both parties wanted, as a matter of fact, to regard the retreat as their success, even though the war was all in all a draw. After the battle between the Commonwealth and Turkey, still in the Khotyn camp, both parties signed the peace preliminaries for whose approval the Commonwealth committed itself to send a grand envoy urgently to Istanbul.

The mission was entrusted to Krzysztof Zbaraski, the Grand Master of the Horse of the Crown, a descendant of an excellent family (the Zbaraski family descended from the Korybutowicz family with whom also the Wiśniowieckis identified). Zbaraski had a huge fortune, which was necessary to finance the mission (the state treasury could not afford it). He was very well educated, he was a recognized expert in military art (warfare was once treated as art) and a great speaker. In 1622, he was 32 years old.

The mission was late. The Turks sent urging letters, but the prince delayed the start of the journey. This was caused, among others, by the dramatic events which took place in the capital of the Ottoman Empire. Annoyed at his Janissaries after the failure of the Khotyn campaign, the Sultan decided to take steps to reform the force. Upset by that, the Janissaries, probably incited by the anti-Ottoman faction, behaved in a way unseen before in the history of the Empire. The Sultan, preparing to leave the capital city, was captured and strangled, and, in addition, the high-ranking dignitaries were deprived of their offices. The mentally ill Mustafa, brother of the previous sultan, was seated on the throne, and the office of the Vizier was successively entrusted to several persons to finally give this important function to the chimerical Giurgi Muhammad, a fierce enemy of Poland.

So the Polish affairs in Istanbul did not look good. Prince Zbaraski feared that the Turks would withdraw from the agreement signed at Khotyn. The mission set off on September 10th, 1622, with a retinue of about 1,200 people, including many merchants who wanted to benefit from customs duty exemption. Irritated by the numerousness of the Polish envoy’s entourage, the Vizier requested customs duty on goods, which had never before been practised in the case of big legations. That was the cause of the first altercation between the Vizier and the envoy, betokening a dramatic course of further negotiations. At Khotyn, two divergent versions of the peace preliminaries were signed. To reach the finalization of the agreement, the arbitrator drew up two versions of the documents, declaring they were identical. In the Turkish version, there was a point including a commitment to pay tribute. The Commonwealth would never have agreed to it because it would be tantamount to the recognition of the Ottoman supremacy. The Polish version mentioned only one-time souvenirs for select dignitaries. At the very beginning of the talks, the Vizier demanded that Zbaraski meet the financial obligations of a tributary, as it was for him one of the conditions of signing the peace agreement. The Prince was stunned to hear such a request, especially that Giurgi threatened with war if in the event of non-payment. So the question of who had won was not originally explicit. It was not until half a century later that the Khotyn legend overgrew with the glory of the Polish arms which as the only one in Europe could effectively resist the ranks of the undefeated Janissaries.

By a lucky coincidence, the Turks lost their copy of the peace preliminaries during the recent rebellion. The Vizier demanded to be shown the Polish copy, but Zbaraski wisely said that he did not have it on him because he was sure that the Porte officials could always extract the relevant document from their archives. Giurgi was embarrassed. Being sure that the Turkish original was lost, the envoy decided to falsify the document, ordering to delete the point requiring the Commonwealth to maintain a permanent ambassador in Istanbul, and he added a point according to which Turkish crews had to leave some frontier fortresses, clarified in detail the obligations of the Porte towards Polish diplomats and ensured a toll exemption at the entrance to the city for the merchants arriving with grand envoys. He also included a provision concerning the appointment of new Pashas in the border districts. Of course, there was no question of any tribute. Interestingly, the Turkish translators who were present at the Khotyn camp swore that the submitted document was authentic. The Vizier was clearly disappointed. He decided to keep the envoy waiting and for three months did not invite him for talks.

At that time, another rebellion broke out in the capital. The dissatisfied Janissaries this time demanded to punish the culprit of Osman’s death whom in fact they themselves had deprived of power. Thus, it turned out that dethroning was one thing while unprecedented shedding of Sultan’s blood was another. The Vizier announced the action of cleansing the city of the assassins, implying that one of the main perpetrators could hide at the Polish envoy’s place. Zbaraski somehow managed to come out of the turmoil unscathed, but the Vizier was already plotting another intrigue. At the council convened by him, he acted as a spokesman for Polish affairs, but persuaded one of the participants to deliver a speech against the Commonwealth. A corrupt adviser said that Zbaraski had certainly come to Istanbul for intelligence purposes, to inquire about the condition of the Ottoman army and of the walls of the capital. Moreover, he doubted whether the legate was sent by both the King and on behalf of the Commonwealth, i.e. the Sejm and Senate. Therefore, he requested to send Zbaraski for a time to Yedikule (Istanbul's famous prison), to take his men into captivity, and to send a messenger to Warsaw to make certain about the King’s intentions.

The “surprised” Vizier of course applauded the advice. Zbaraski was informed by the translator in guarded words about what had happened. The members of the mission were paralyzed with fear. The Prince ordered his courtiers to prepare to fight off the pagans and stayed awake all night, awaiting the progress of events. In the morning, instead of an expected assault, a Turkish messenger brought quite unexpected news of overthrowing the Vizier and electing a new one. The new Vizier, Mere Hussein Pasha, turned out to be a very friendly person both to the envoy and his mission. In the beginning, Zbaraski did not trust him, because before the Prince’s arrival in Istanbul it was on Hussein’s initiative, as rumour had it, that Samuel Korecki, the famous borderland adventurer who, owing to his willful though having the King’s silent support expeditions to Moldova, achieved knightly fame in the Commonwealth, had been murdered in Yedikule. Nevertheless, the Vizier convinced the Prince with the declarations of his friendly disposition towards Poland. After exchanging the mandatory gifts, the negotiations went rather quickly. Both parties sought to complete the mission as soon as possible, because the city spread rumours about the planned expedition against Persia (and therefore the Turks wanted to secure peace in the North), as well as another coup being prepared by the Janissaries (the envoy did not want to risk another change of fortune). Having agreed the wording of the Treaty, the Sultan gave the farewell audience and the Grand Vizier threw a banquet at which both men made pledges of mutual friendship. The legate did not forget then to remind about the Polish prisoners of war held in Istanbul. The Vizier agreed to the buy-out of Hetman Stanisław Koniecpolski and Łukasz Żółkiewski, Hetman Stanisław Żółkiewski’s nephew, who were captured after the Cecora tragedy. Also Korecki’s body was secretly taken. Having arranged the most urgent matters, the Prince hastily left the Turkish capital, taking, however, a circuitous route through Transylvania to avoid the reluctant Moldovan Hospodar. On the way, Zbaraski learned that Giurgi was reinstalled as the Vizier.....

The turbulent mission was described in verse by Krzysztof Zbaraski’s private secretary Samuel Twardowski in his peregrination epic: “Przeważna legacyja Krzysztofa Zbaraskiego od Zygmunta III do sołtana Mustafy”, (“The Important Mission of His Grace Duke Krzysztof Zbaraski from Sigismund III to Sultan Mustafa”) published by R. Krzywy, Warszawa 2000.

We would like to inform that for the purpose of optimisation of content available on our website and its customisation according to your needs, we use information stored by means of cookies on the Users' end devices. You can control cookies by means of your Internet browser settings. Further use of our website without change of the browser settings means that you accept the use of cookies. For more information on cookies used by us and to feel comfortable about this subject, please familiarise yourselves with our Privacy Policy.

✓ I understand