Martino Altomonte was one of the primary painters of Jan III Sobieski. At the royal court of artists, he was assigned the significant part of a co-creator of the monarch’s official iconography, rooted in his military exploits.

It is commonly assumed that Altomonte was born 8 May 1657 in Naples, although this is not fully confirmed. The date of his birth can sometimes be put at 1659 based on a handwritten inscription on one of his later canvasses, while certain scholars go as far as to deny the painter’s Italian origins, on the assumption of his kinship with the Tyrolean family of Hohenberg — given that ‘Altomonte’ is simply a Latinised variant of that German name.

Altomonte spent his period of learning and artistic formation in the 1670s in Rome, which at that time reached the apex of its artistic development. According to historical records, at the age of around 15 the painter joined the workshop of Giovanni Battista Gaulli, known as Baciccio — one of the foremost creators of monumental painting and the author of venerated panel paintings, an heir to the artistic traditions of High Baroque defined in the milieus of Gianlorenzo Bernini and Pietro da Cortona. After most likely five years of education and work under Baciccio, Altomonte probably continued to learn his trade in Rome, perhaps — as is sometimes suggested — under Giacinto Brandi, an outstanding contemporary painter, and finally under Carlo Maratta. The latter would soon become not only the most revered painter in the Eternal City, but also a universally acknowledged authority in all artistic matters, partially responsible for adding a characteristic classical tinge to the art of late seventeenth century. Thus, the young Altomonte found himself under the influence of two crucial tendencies shaping Roman art at the time: the expressive, sensual painting meant to deeply affect the viewer (whose basics he likely apprehended from Baciccio) and the reserved, classical art, reliant on a repertory of more rigorous formal devices (represented primarily by Maratta). Traces of these twin inspirations are evident in Altomonte’s numerous later works. Furthermore, it is more than likely that during his Roman years the painter remained tied to the milieu of the local Accademia do San Luca, an institution gathering young adepts of painting, sculpture, and architecture, and establishing artistic norms (incidentally, all his likely teachers in Rome headed the Accademia at one point or another).

Thus formed, the painter — whose young age belied the experience of the time spent in the flourishing artistic environment of Rome working under the most distinguished artists active in the city in that period — was summoned to the Commonwealth. This most likely happened in 1684, a seminal year for the development of Jan III’s court of artists. It can be assumed that the King, given his sensitivity in matters of art and quite keen awareness of contemporary artistic trends, was at that time on the lookout for another well-educated painter for employment in the royal residences. Understandably, he turned his attention to the Eternal City, a frequent source of artists for Sobieski’s patronage, and a city which the King had visited personally at an earlier stage of his life.

Most authors agree that Altomonte’s arrival to Poland was facilitated by Marco d’Aviano, a Capuchin in Jan III’s confidence who played a major part in preparing diplomatic grounds for the anti-Ottoman coalition. However, it is not impossible that the duty was taken up by someone else, such as — as has been suggested — Jan Kazimierz Denhoff, who represented Jan III in Rome at that time and received a cardinalship from Innocent XI in 1686. It is also not unlikely that relations between the painter and the Polish monarch were initiated with the aid of the artist’s peers. After all, the period of Altomonte’s arrival to Poland coincided with the return of Jan Reisner and Jerzy Eleuter Siemiginowski — two artists who shared Altomonte’s association with the Accademia di San Luca and went on to find employment in decorating the palace at Wilanów — from royal scholarships to Rome. Altomonte himself received commissions paralleling those of his two colleagues, though they seem to have primarily involved the residence in Zhovkva.

Jan III put considerable trust in Altomonte, assigning him the task of developing his new battle iconography. The King, whose wartime achievements had been consistently downplayed by Imperial propaganda since immediately after the victory at Vienna, was doubtless keenly aware of the significance of testifying to his earthly achievements. Interestingly, the painter commissioned to perform this demanding task did not have much experience in battle painting at the time of his arrival to Poland. His works — not all of which were equally successful — are marked with a constant pursuit of proper compositional arrangements.

Sadly, most of Altomonte’s battle paintings are presumed to have perished. In all likelihood, his earliest works in this vein were designed for the residence in Zhovkva. Based on an archival note, it is assumed that a message citing the lending of eight battle paintings to King Stanisław August Poniatowski by Karol Stanisław Radziwiłł, then owner of Zhovkva, in 1778, concerns precisely these works. They were borrowed for copying in Warsaw and were supposed to be returned afterwards, which apparently never happened. Before World War I, what remained of them was putatively stored in the attic of the town hall in Lviv. Two of Altomonte’s monumental battle paintings survived to our time: The Battle of Vienna and The Battle of Parkany, made for the collegiate church at Zhovkva, where Jan III intended to create a pantheon of the glory of his family (the paintings are the property of the Lviv Art Gallery; in 2007–11, they underwent conservation in Poland in preparation for placing in the intended location, which eventually did not occur). Both works were produced only in 1694, late editions of compositions which the artist has been perfecting ever since he found himself in the King’s employ. The earliest studies for The Battle of Vienna are known from two sketches by the painter: a drawing, most likely an initial version of the composition (currently at the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest) and an oil painting, signed and dated 1685 (preserved at the monastery of Regular Canons in Herzogenburg, Lower Austria).

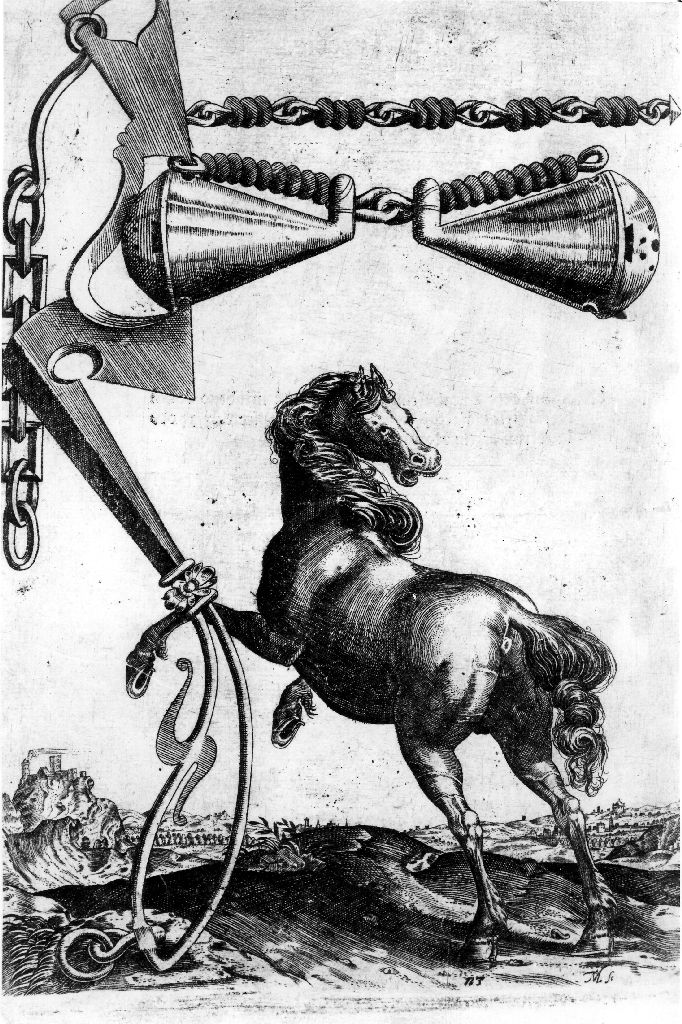

Altomonte’s battle paintings were not loose adaptations of recent events. It is (apparently correctly) believed that the King, known for his deep interest in the progress of the works he commissioned (e.g. the construction and decorative works at the Wilanów palace), was personally involved in the production of the paintings. The painter was evidently asked to faithfully reproduce the scenery of the battle down to the smallest details. For instance, he must have been granted access to the spoils of war brought back from Vienna and held in the King’s estates. This is proven by the so-called sketchbook of Melk (held in the library of a monastery in that city), which includes numerous drawn notes by Altomonte, for instance, presenting Turkish tents and details of armament. The drawings may have been produced during a showing of the Vienna spoils organised in Zhovkva on 25 July 1684 for invited guests, among whom were the Papal Nuncio and a Venetian envoy. Attention to the details of the battle was not limited only to the scenery and particularities of clothing and armament — it also involved minor, marginal episodes. A frequently cited minutia found deep in the background of Zhovkva’s The Battle of Vienna is the figure of a janissary cutting off the head of an ostrich in front of the vizier’s tent. The detail was recorded by Sobieski in a letter to Marie Casimire, written during the night after the battle. This illustrates the painter’s journalist-like attention to detail, most likely motivated by the King’s own demands. Most likely, the King had also suggested the inscription on the ribbon held by an angel in the same painting: Ne quando dicant gentes ubi est Deus eorum (Wherefore should the nations say, where is now their God), a quote from Psalm 113; the words were cited in the King’s aforementioned letter.

Altomonte’s battle scenes — particularly the different redactions of The Battle of Vienna — are rooted in Roman painting. One of the possible direct analogies is The Battle of Alexander and Darius by Pietro da Cortona (Rome, Musei Capitolini), which may have served as a source for the painter’s numerous formal gestures. Modern iconographic traditions also motivated the use of certain motifs: the image of Sobieski trampling a Turk replicates the depiction of a horseman in the well-known fresco The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple by Raphael (found at the Vatican palace). Altomonte’s another source for this fragment of the painting may have been the so-called Apotheosis of Jan III, produced by Jerzy Eleuter Siemiginowski and reproduced in graphical form by Charles de la Haye, proof positive of a cooperation between the two royal artists.

Of course, battle scenes were not Altomonte’s sole speciality. He also successfully engaged in portrait and religious painting. Sadly, no portraits attributable to him have been identified. However, perfect examples of his altar paintings have survived, for instance in the side altars of the pilgrimage church at Święta Lipka. Abraham’s Offering, held at the Diocesan Museum in Tarnów, also counts among Altomonte’s finest achievements.

Altomonte settled in Poland for good. Toward the end of 1690 in Warsaw he married Barbara Dorota Gierkien, considered to be either French (with the last name properly spelled Guerquin) or a native of Königsberg. Over the next few years, the birth of five of his children was recorded, including Bartolomeo (b. 1694), later a famous painter in Vienna. After Jan III’s demise in 1696, the painter probably continued to work in Warsaw. Yet, few of his paintings from that period remain. At different times, he accepted commissions from the Wodzickis (Wawrzyniec Wodzicki, Deputy Cup-Bearer of Warsaw, and his wife, Anne, ordered at least twelve canvasses from him), the Voivode of Płock Jan Dobrogost Krasiński, perhaps also Hetman Stanisław Jabłonowski, and later, members of the Radziwiłł family, among others. As late as 1699, together with Jerzy Eleuter Siemiginowski, he prepared theatrical decorations at the Warsaw Castle for August II. Studies often repeat the claim that painter Altomonte was employed in decorating the palace at Wilanów; while the claim itself is legitimate, his possible works at Wilanów have not been identified so far.

Early in the eighteenth century Altomonte departed from Poland and moved to Vienna (he is sure to have arrived there by January 1702). The departure may have been prompted by events of the Great Northern War, which entered the Commonwealth as early as 1701 (the forces of Charles XII traversed Poland early in 1702, taking Warsaw in May and Cracow in July). One might also suppose that he sought to profit from the lucrative commissions in the Imperial capital which entered a period of boom following the removal of the Turkish threat. The painter could expect that his previous works in Poland and the position of a court painter would serve as sufficient recommendation. It seems, however, that it took him a while to achieve recognition. His first works completed in Vienna date to only several years later. In the same period, the painter entered the official structures of the artistic societies of Vienna, becoming in 1707 a member of the Academy that recently began to operate under Imperial patronage, and also an assistant to its creator and director, Peter Strudel. Over the following years, Altomonte received a series of prestigious commissions, including painted decorations at the Bishop’s palace in Salzburg (for Bishop Franz Anton Harrach, since 1709) and in the Lower Belvedere in Vienna (for Prince Eugene of Savoy, 1716). He also authored numerous altar works, for instance for several churches in Vienna (among others, the cathedral and church of Saint Peter) and monastic churches, particularly of the Cistercians (at Zwettl and Lilienfeld, among others) and Augustians (at St. Florian and St. Pölten, among others). In many of his later works, he employed his son, Bartolomeo. In 1719 or 1720 Altomonte moved for a few years to Linz, and then became attached for a longer period to the Cistercian abbey in Heiligenkreutz near Vienna. He continued to accept commissions from the Commonwealth (including Lviv and Warsaw). He died in Vienna on 14 September 1745.

Translation: Antoni Górny