Both families became joined by marriage in 1719 when the teenaged Princess Marie Clementina Sobieska (1701-1735) made her politically dangerous and physically treacherous journey from Oława to Rome and married the exiled James III/VIII (1688-1766) (VIII as King of Scots, III as King of England and Ireland). By then, both families had failed to maintain their respective thrones. Not long after, both became extinct, the last generation of each represented by a daughter with the same name and title: Charlotte Sobieska, Duchess of Bouillon (1697-1740) and Charlotte Stuart, Duchess of Albany (1753-1789).

This essay does not attempt to describe each of the many fascinating exhibits in this wonderful exhibition. It selects just a few which are particularly rare, unusual, or unique.

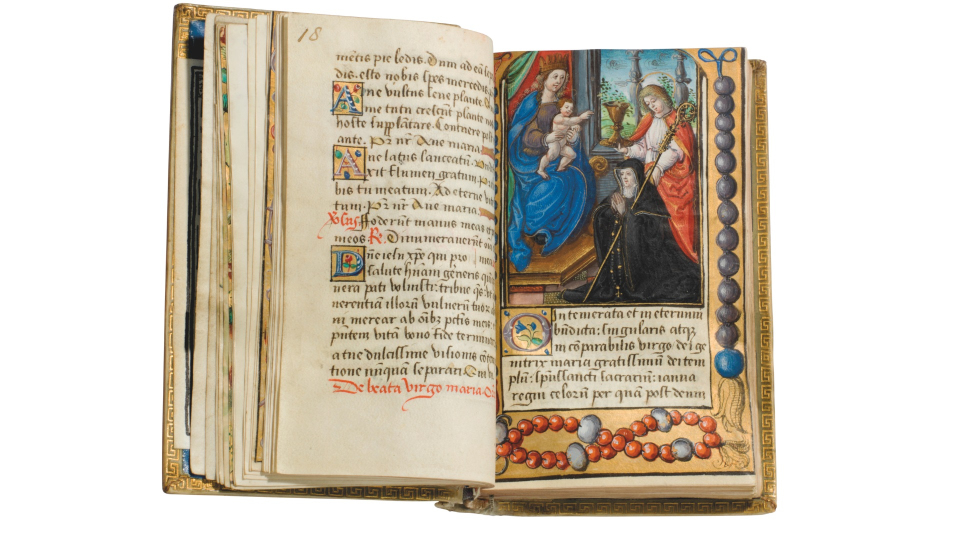

The book of hours which belonged to Mary Queen of Scots’ (1542-1587) dates from 1534-40. It symbolically opens the exhibition, being the earliest exhibit, and because it is the work of ‘The Master of Archbishop François de Rohan’, one of the greatest artists working at the Court of the French king, François I. Paris was then the leading centre for such works on parchment which were extremely expensive and already being replaced by printed volumes. It also symbolically closes the exhibition. Because the only member of the last generation of the Stuarts was Charlotte Stuart, the father of whose children was Archbishop Ferdinand de Rohan (1738-1813), from the same great Franco-Breton family of sovereign princes as Archbishop François de Rohan (1480-1536).

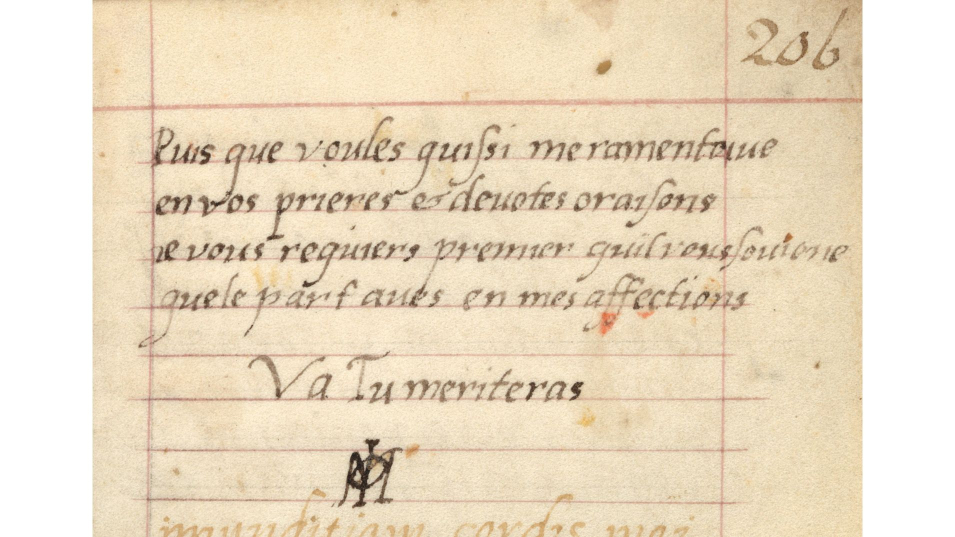

Mary Queen of Scots’ book of hours was commissioned by her maternal grandmother’s sister, Louise de Bourbon-Vendôme (1495-1575), shortly after 1534 when Louise was appointed Abbess of Fontevraud. The book of hours, the binding and parchment of which was recently cleaned and restored by Anna Kowalewska, not only contains tens of magnificent illuminations, but also a unique inscription written by the teenaged queen herself. She signed it with the monogram M combined with F (as Φ) for her husband. The inscription reveals that the book of hours was given to Mary by her great-aunt at Fontevraud around the time of her marriage in 1558 to François II who was crowned King of France in 1559, but died suddenly in 1560. It was his death which triggered the grief-stricken Mary’s return to Scotland. It is extraordinary to think that this book of hours travelled with her on that dangerous journey by sea from Calais to Edinburgh’s port of Leith, where she landed on 19 August 1561. That marked the end of her happy youth in France and the beginning of the long tragic final chapter of her life which ended with her execution in 1587. Her beheading was a shameful act, orchestrated by her Protestant cousin Elisabeth I of England, who feared Mary’s potential claim to the English throne, which Roman-Catholics believed was stronger than her own.

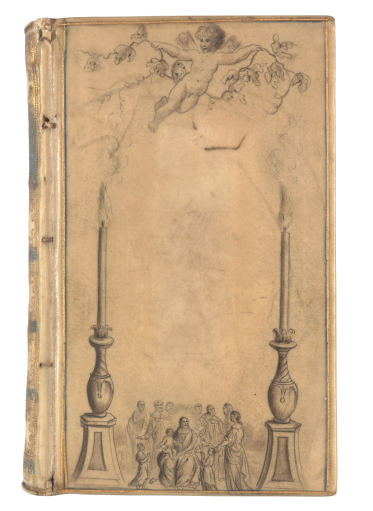

Mary’s book of hours has another exceptional aspect. It was rebound in the late 18th or early 19th century by the famous English bookbinders, the Edwards family of Halifax, and the narrative scenes are painted en grisaille under vellum, rendered translucent by a special method patented by James Edwards in 1785.

There are only four other books of hours which can be said with certainty to have belonged to Mary Queen of Scots. But none were commissioned by her family and given to her as a wedding present. All were old when acquired, dating from the 15th century, and have origins unassociated with the queen. The one on display in this exhibition is also unique in being the only one of Mary’s books of hours still in private hands. The other four belong to the Huntingdon Library in San Marino (California), the Ruskin Gallery in Sheffield (UK), the British Library in London, and the National Library of Russia in St Petersburg.

Mary is a key figure in this exhibition. She was the last member of the first Stuart dynasty, being the only legitimate child of James V, King of Scots. He died when Mary was six days old, whereupon she became queen. She then founded the second Stuart dynasty in 1565 when she married Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, from the family’s junior line of the Earls of Lennox. In fact, Mary and Henry were close cousins. They had a common grandmother. She was Margaret Tudor, the sister of Henry VIII of England. And in 1566 Mary gave birth to a son who in 1567 in Stirling was crowned King of Scots as James VI, and in 1603 at Westminster was crowned King of England and Ireland as James I.

King James I/VI died in 1625. Later that century, his grandson, James II/VII, lost the Stuarts’ three thrones of Scotland, England and Ireland when his second wife, the Roman-Catholic Queen Mary of Modena (1658-1718), gave birth in June 1688 to a male heir, James Francis Edward Stuart, the future husband of Clementina Sobieska. The Catholicism of the heir to the throne and King James’ unpopular policy of equal rights for Catholics, prompted his Protestant son-in-law William of Orange (who was also the son of King James’ sister Mary) to invade England in November 1688 with an army of thirty thousand men. In late December James II/VII fled into French exile and the protection of his cousin Louis XIV who provided the Stuarts and their court with his place of birth, the vast Château de Saint Germain-en-Laye. It was there that the portrait of the four-year-old future King James III/VIII was painted by Nicolas de Largillierre. And the story behind this portrait is fascinating.

It was commissioned in the Spring of 1692 by the prince’s mother to celebrate him having been made a knight of the Order of the Garter, England highest order of chivalry. It is the third of five painted by Largillierre during the period 1690–95, of which only three survive. Both of the main figures were painted in the studio. But to provide elements for his composition the artist made sketches from the gardens of the Château Neuf at Saint-Germain. The Stuarts themselves lived in the adjacent Château Vieux. On the left is the white retaining wall and stone balustrade of the upper terrace. At the left end of the parrot’s body is the roof of the pavilion where Louis XIV was born. Below the wall is a statue of an antique figure and, in front, the tiny figures a horse and two men in court dress looking at the prince. They are almost certainly King James and King Louis. The youth beside the prince stands in front one of the baroque fountains on the gardens’ second level. James appears as Prince of Wales, his white feathers being the heraldic crest of that title. He is also wearing the blue riband of the Order of the Garter. His right hand holds a poppy, two with seed pods, a symbol of sleep. Looking on is a parrot, symbolic of childhood, but also of the Virgin Mary, and thus Catholicism. In front of the older boy lies bindweed which represents loyalty.

The youth beside the prince is Walter Strickland (1675-1715), the eldest son of Winifred, Lady Strickland who accompanied Queen Mary with the newly-born Prince James when they fled England and crossed the Channel in December 1688 after William of Orange’s invasion. The painting represents Lady Strickland’s loyalty, as well as her duty as governess of putting the infant prince to sleep at night. Unusually, Largillierre enlarged the canvas on all sides. Proof of this is in the fact that the canvas pieces are all of the same date and the paint pigments are consistent throughout. In order to confirm that he was the painter, not only of the original central canvas, but also of the enlarged parts, Largillierre placed his signature over one of the seams joining the pieces of canvas.

Infra-red reflectography reveals that the central rectangle of canvas was originally a portrait of James alone. This is confirmed by Gérard Edelinck’s engraving of 1692 which shows only the prince. But immediately after, something made Queen Mary change her mind about the composition. The only element of significance on the enlarged part of the canvas is the figure of Walter Strickland. The reason why the queen suddenly wanted him included, was that in the late summer of that year Lady Strickland applied to leave court, which she did in October, to go and be with her ill husband, Sir Thomas, at the Convent of the English Poor Clares in Rouen. Therefore Queen Mary instructed Largillierre to include Lady Strickland’s son in the portrait, so she could give the painting to her friend as a memento.

To do this Largillierre had to enlarge the canvas. Yet he was limited in how much he could do so, as he could not allow the central figure of James to become disproportionately small. Yet Walter was a teenager and much larger. So the artist positioned him snugly alongside James, with his back to the viewer. This avoided drawing attention from the painting’s principal subject, which was James. Walter’s graceful pose of leaving is also a reference to the Stricklands’ departure from court, and is balanced by a colourful parrot and sky. In reconciling these problems Largillierre transformed what had previously been the straightforward portrait seen in Edelinck’s engraving, into a composition of real genius.

Because so few have survived, the Sobieski-Stuart exhibition is exceptionally lucky to have on display not one, but two pairs of portraits of King James III/VIII with his queen, Princess Clementina Sobieska. The first pair was painted by the Scottish artist William Mosman in the Autumn of 1733 at the Stuarts’ Palazzo del Re in Rome. It is copied from the originals of 1719 by Francesco Trevisani. We know that James liked his portrait, because in 1722 he gave permission to his court painter Antonio David to copy Trevisani’s portrayal of his face and include it in David’s own portrait of the king. Originally, Trevisani made three pairs: one for the Stuarts, one for his patron Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni, and one for John Erskine, the Jacobite Duke of Mar. Of them, none of the portraits of Clementina have survived. Mosman made his copies in 1733 for the distinguished Stuart supporter George Keith, 10th Earl Marischal. In 1735 Trevisani’s pupil Francesco Bertosi made another pair. This time for a less important Jacobite, Captain John Urquhart of Craigston and Cromarty. Of Bertosi’s pair, only the portrait of Clementina has survived, and is in Edinburgh’s Scottish National Portrait Gallery. Therefore, Mosman’s 1733 portraits are unique, because they are the only surviving pair. And Mosman’s portrait of Clementina is the only one painted during her lifetime by a Scot (apart from John Smibert’s copy of the 1721 portrait of her by Girolamo Pesci). Yet another aspect of Clementina’s portrait is extraordinary. The exhibition has on display, not only her portrait with a gold watch on the table. It has the gold watch itself! And it is no ordinary watch.

The watch was made in London in 1718 by Isaac Duhamel. Its chased and repoussé gold work is replete with symbols. Its cartouches contain weapons, two flaming hearts pierced with arrows, two doves kissing, and fruit as a reference to hoped-for progeny. Nothing could be more appropriate for James and Clementina’s marriage in 1719. And it was a wedding present for the queen from Frances Erskine, Duchess of Mar.

There is also the principal allegory of the back cover of the watch’s outer case. Set against an architectural backdrop, a cupid with wings holds a bow on the left. In the centre is a woman giving a flaming heart to the man on the right. He is wearing a sash which falls from the left shoulder and is fastened at the right hip where something is attached. It is the Order of the Garter, with the jewel known as the ‘Lesser George’ attached at the right hip. His left hand is reaching for the branch of the laurel tree behind, whilst his right hand is placed on a lance. Attached to the laurel tree are a helmet with a plume, a commander’s baton, a sabre and a horse’s stirrup. All are symbols referring to Clementina’s grandfather King Jan III Sobieski who had earned his laurels battling against the Turks, who personally commanded the Polish heavy cavalry which defeated the Turkish army at Vienna in 1683, and whose principal weapons were the lance and sabre. All these attributes can be seen on the well-known portrait of the Polish king dated 1673–77 attributed to Daniel Schultz. The male figure in Duhamel’s repoussé work is even dressed in the same military attire as in Schultz’s portrait, displaying leather straps falling from the waist, and karacena armour to protect the breast, with epaulettes, emerging from which can be seen the turned up sleeve of the under-garment. These references to Sobieski’s military achievements were especially appropriate at the time the watch was made. Because, with Spanish support, King James was about to launch another attempt to regain the Stuarts’ thrones by force of arms.

Attached to queen’s watch are two seals. One is engraved on a white stone with a Scottish thistle with two flowers, one for James and one for Clementina, a symbol of the Stuarts’ right to the Scottish throne. It dates from 1718-19. The second is also on a white stone. It is set in gold with a royal crown and engraved with a rose and two buds. This is the Stuart emblem of the white rose, the flower in full-bloom being for James, the two buds signifying his sons Charles and Henry. It dates from 1725 or shortly after. Finally there is the winder. It has a finial with a bloodstone engraved with an heraldic composition based on the Sobieskis’ coat of arms Janina and a deer’s head with antlers from the arms of King Jan III’s French wife, Marie-Casimire de La Grange d’Arquien, known as Marysieńka (1641-1716).

The second pair of portraits was painted in Rome by Antonio David in 1730. The artist’s earliest Stuart portrait dates from 1717 and was of King James who appointed him official court painter a year later. David’s 1730 portraits of James and Clementina were copied from the lost originals by Martin van Meytens, painted in 1725 to celebrate the birth of the Stuarts’ younger son Prince Henry Benedict Stuart, Duke of York, the future cardinal. In 1727-28 the Stuarts commissioned a number of copies of Meytens’ originals by the minor English artist E. Gill. But they resigned halfway through, due to the poor and uneven quality of Gill’s work. King James’ finances were not then in good condition. But by 1730 they had improved considerably, so he ordered a small number of copies of Meytens’ originals by David. The pair in the exhibition are the only surviving examples. And James and Clementina very much liked these portraits. because his hung in her bedchamber, and hers in his.

They were described in 2008 by the David authority Dr Simona Capelli as ‘marvelous portraits’, and Clementina’s is the most beautiful portrayal of her ever made. For this there is a special reason. Clementina’s health had been declining since 1726 and by 1730 her eating disorder had resulted in her looking thin, tired and haggard. David was the only artist who had known her closely since her arrival in Italy in 1719. Moved by the queen’s damaged health and sad appearance, his portrait of 1730 restores to her the beauty and vitality of the once-brilliant charismatic queen whom he had known for over a decade. In fact, he made her look even more beautiful than on Meyten’s original. This can be seen by comparing David’s portrait with later copies made from the original. Lodovico Stern painted a copy in 1740, Louis-Gabriel Blanchet in 1741, and Domenico Duprà in 1742.

Stern’s version (also in the exhibition) served as the model for the mosaic by Pietro Paolo Cristofari (1685-1743) on the 1742 monument to the queen in St Peter’s, designed by Filippo Barigioni (1672-1753) and sculpted by Pietro Bracci (1700-1773). The Registro degli Ordini della Fabbrica di San Pietro records that the Vatican paid Stern 40 scudi for his copy. In fact it differs slightly from the original. Cardinal Lanfredini considered Clementina’s décolleté inappropriate for St Peter’s. However, Pope Benedict XIV approved it. But only after the lace of the queen’s dress had been turned up.

Of exceptional importance, both with regard to artist and sitter, is Rosalba Carriera’s stunning portrait of King James and Queen Clementina’s eldest son, Prince Charles Edward Stuart, known to history as Bonnie Prince Charlie. It portrays the sixteen-year-old future leader of the legendary 1745 Jacobite Rising who came so close to regaining for the Stuarts their thrones of Scotland, England and Ireland. Rosalba’s pastel was exhibited in 2019 at the National Museum of Scotland, in 2022 at Scotland’s West Highland Museum, and in 2023 at Dresden’s Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister. It was also the subject of Professor Edward Corp’s 2020 article in the British Art Journal entitled The Recently Discovered Portrait of Prince Charles Edward Stuart by Rosalba Carriera (1673-1757). In it he describes Rosalba as ‘probably the best, and surely the most famous artist, male or female, who ever painted Charles’ portrait’. The portrait is not only exquisitely beautiful, impressionistic in the brilliant rendering of the pastel, in such perfect condition that it might have been painted yesterday, but is of importance for several other reasons.

The National Gallery in London writes that ‘Rosalba Carriera’s mastery of the pastel medium helped transform it into a serious and highly admired art form’. Washington’s National Museum of Women in the Arts describes her as ‘one of the most successful women artists of any era’. In the eighteenth century, Europe’s fashionable elite was desperate to have a portrait by Rosalba. The Stuarts’ enemy, the Hanoverian King George III of Great Britain, admired her greatly and had an important collection of her work. So too did Clementina Sobieska’s cousin, Emperor Charles VI. But the largest collection of all was acquired by King Augustus II of Poland who created Das Kabinett der Rosalba in Dresden – which still has largest collection of her works in existence.

Rosalba painted Prince Charles in Venice in June 1737 during his extraordinarily successful tour of the northern Italian states. Charles and his chaperon, James Murray, Lord Dunbar, arrived in Venice on 28 May and left on 10 June. This allows us to date the portrait to the first week of that month. It is unique as the only portrait of Charles, prior his departure from Rome to France in 1744, which does not have a companion portrait of his younger brother Henry. It is also the last portrait of him prior to the cutting off of Charles’ hair on 3 August 1737, about which he was delighted, that being a sign of adulthood.

Charles’ tour of the northern Italian states was politically very important. It was also the first time he felt himself to be his own man, not overshadowed by his patronizing father. His new-found confidence shines through in Rosalba’s portrait. It was in stark contrast to the prince’s spoilt childish behaviour in Rome, which was one of the main reasons his father sent him away, hoping the experience might make him might grow up a little. Contrary to his expectations, King James’ hopes were exceeded beyond his wildest dreams and the impression the charismatic Charles made on all the courts of Northern Italy was sensational.

It is relevant that Rosalba’s portrait was painted away from Rome. As a result it was free from King James’ habitual influence over the artists he commissioned. This, and the fact that only the very best painters could be relied upon to capture the truest of likenesses, means that Rosalba’s image of Charles is one of only three surviving portraits which we can be sure show the prince as he really was at the time. The other two are Allan Ramsay’s oil on canvas portrait of late October 1745 at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh, and Hugh Douglas Hamilton’s oil on paper of 1786 which is also on display in this exhibition. The latter portrait is important, because it is Hamilton’s original painting, done from life, from which he copied all his subsequent versions in pastel and oil. And though Charles looks old and tired, his health damaged by alcohol, this portrait dates from the happiest years of his life since the trauma of his failed Rising of 1745. It began when his daughter Charlotte came from Paris to live with him in October 1784, firstly in his palace in Florence, then from December 1785 until the prince’s death in January 1788 at the Stuarts’ Palazzo del Re in Rome.

In Venice there were no portraits of the prince by other artists to influence Rosalba. She had only the sitter himself upon which to base her portrait. That was also true of the portrait of Charles painted hastily by Allan Ramsay in Edinburgh during the 1745 Rising itself, just prior to the departure of the prince’s army for England at the beginning of November. This absence of comparative portraits is important, because of the instructions King James usually gave his artists. One example of this interference is the pair of portraits of Prince Charles and Prince Henry painted by David in 1729. In this case the king told David to age both sons by four years so the images would remain current for some time, allowing further versions, miniatures and engravings to be made and sent to Jacobite sympathisers. Consequently, David’s 1729 portraits of Charles and Henry do not show them as they looked at the time. They show them as David imagined they would probably appear four years later.

In fact, James didn’t like Rosalba’s portrait. And while Charles was still away with Dunbar, the king ordered pastels of himself and Henry by Jean-Ėtienne Liotard which, though lacking Rosalba’s genius, he personally preferred. And when Charles returned to Rome, his father instructed Liotard to complete the set.

Why, we may ask, did James not like Rosalba’s portrait of his son? Dunbar’s correspondence reveals that Charles had put on quite a lot of weight during his time away from Rome. Was that the reason? On the other hand, the Getty Museum writes of Rosalba’s ‘interest in rendering the sitter’s inner psychology’. Of herself Rosalba said ‘I have so long been accustomed to studying features, and the expression of the mind by them, that I know people’s tempers through their faces’. Did her portrayal of the prince’s confident posture and fearless gaze disturb the king, whose stoical reactive character was so different to that of his dynamic proactive son? Did James feel something about Rosalba’s portrait of Charles which intuitively worried him, some harbinger of the dramatic and tragic events of his son’s 1745 Rising which would soon unfold?

Piotr Pininski, together with Professor Edward Corp, is a consultant to the Sobieski-Stuart exhibition at Wilanów. He is a graduate of Sotheby’s Institute of Art and has lectured internationally on the last Stuarts for institutions such as the National Trust for Scotland. He has been a guest speaker at the Edinburgh International Book Festival and is the president The Lanckoronski Foundation, a member of the advisory board of the National Art Gallery of the Ukraine in Lwów, an advisor to the director of the Wawel Royal Castle in Kraków, and to the Ossolineum in Wrocław. He is a member of the Biography Committee of the Polish Academy of Learning (Polska Akademia Umiejętności), co-curated the 2022 exhibition on the Stuarts at the West Highland Museum in Scotland, and is the author of various publications on the Stuarts, his most recent book being Bonnie Prince Charlie – His Life, Family, Legend, published by National Museums Scotland in 2022.