History of the Garden Galleries

The construction of the Garden Galleries, which formerly linked the towers and currently the wings of the Palace to its main body, began in 1681, motivated primarily by the need to enhance the monumental character of the architecture of the Palace. Information regarding the construction of the Galleries can be found in letters from the architect Agostino Vincenzo Locci to King Jan III; on 29 August 1681, Locci informed the ruler that the masons were “beginning works on the foundations for the gallery.” Based on this correspondence, we can surmise that constructions works proceeded at a rapid pace and may have been completed in the first half of 1682. No unambiguous sources are known, however, which would confirm the moment at which finishing and decorating work began on the interiors.

Initially, both galleries were given the form of Roman triumphal arches on their courtyard-facing sides, creating a majestic entrance to the garden. Their allegorical and symbolic decorative elements played an important role in the narrative, one which extolled the glory of the monarch. From the garden-facing side, the galleries were given the form of open garden pavilions, drawing on the designs of Michelangelo for the palaces of the Capitoline Hill in Rome.

The North Gallery

A key aspect of the appearance and function of these spaces is their connection with nature and openness to the garden. The theme of the artistic decor of both galleries is provided mainly by the frescoes on the walls and ceilings, the stucco work on frames and dividers surrounding them, and the bas-relief figurative plasterwork, although architectural details such as capitals of pilasters and cornices add to this as well. These integrated painted and plasterwork decorative elements were created in a particular order; first, the stucco decorations were completed, and only then did the fresco painter begin. In the North Garden Gallery, two painters worked: Michelangelo Palloni, invited for the job by King Jan III, and Giuseppe Rossi, who served the subsequent owner of the Wilanów Palace, Elżbieta Sieniawska. From the garden side, the façades of the gallery are adorned with fresco paintings illustrating scenes from the Odyssey and the Aeneid as well as with statues in niches symbolising the Earth and the various districts of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The interior walls and ceilings of both galleries were decorated with illusionist frescoes presenting the Story of the Maiden Psyche. These create the illusion of direct contact with natural landscapes and life-sized figures of the characters from the story. The frame for the painted scenes is provided by illusionistic, painted columns based on the columns from the façades of the galleries. They may be narrower, as they increase the impression of distance. The illusionistic paintings combine the world of myth with the real world.

Substantial changes in the galleries were introduced by the next owner of the Palace, Elżbieta Sieniawska, who bought the deteriorating residence from Konstantyn Sobieski in 1720. The expansion of the Palace with side wings conducted by the architect Giovanni Spazzio in the 1720s reinforced the function of the galleries as corridors open to the garden. It is also known that in the years 1724–1726, the painter Giuseppe Rossi painted numerous frescoes in the interiors of the Palace and is also likely to have supplemented Palloni’s work in the Garden Galleries. It is understood that Rossi was the creator of the frescoes with images drawing on statues from antiquity on the western wall of the North Gallery, meaning that by the 1710s the portals leading from the main courtyard had already been bricked up. In the early 1720s, the stucco artist Francesco Fumo was also active at Wilanów, the artist who together with Pietro Comparetti decorated the new rooms of the residence and made repairs to the older decorations.

During the period when the residence was in the possession of Maria Zofia Czartoryska (from 1733 to 1771), and later of her daughter Izabela Lubomirska (to 1799), both galleries were renovated, though without serious alterations. The subsequent owners of the Palace, Stanisław Kostka and Aleksandra Potocki, opened the interiors of the royal residence along with its collection of European and Far Eastern art to the public in 1805, creating the second museum to be established in Polish lands, after the Temple of the Sibyl in Puławy. During the years 1819-1821, the North Gallery was transformed for the purposes of exhibiting the collection, something which had a significant impact on the arrangement of the interiors. In 1820, the spaces between the columns were bricked up, leaving only small window openings, and thus creating a closed space. In the 19th century, the pilasters, capitals, dividers and architectural details on the walls of the North Gallery were completely chiselled off and the polychrome paintings were covered over, leaving a plain surface appropriate for displaying the numerous paintings in the collection. Unfortunately, the plastering over of the frescoes seriously damaged them; the surfaces of the paintings suffered numerous hammer blows, leading to the loss of a large part of the painted layer. Some of the paintings survived with a maximum of 20-30% of the original intact. The walls were painted in the then-fashionable colour of Pompeii pink, used to create a museum backdrop for the paintings. Next, in the 1850s, the Berlin-based painters E. Bürger and C. Hintze painted over the 17th-century frescoes on the ceiling of the gallery with monochromatic ornamental compositions with the likenesses of famous painters. In the last quarter of the 19th century, Aleksandra Potocka, the next owner of the Wilanów residence, made further alterations to the interiors; she divided the northern part of the gallery with a wall, creating in 1875 the Lapidarium, a cabinet intended for the exhibition of ancient statuary. She also commissioned Antoni Strzałecki to conduct far-reaching transformations of Palloni’s paintings in the South Gallery.

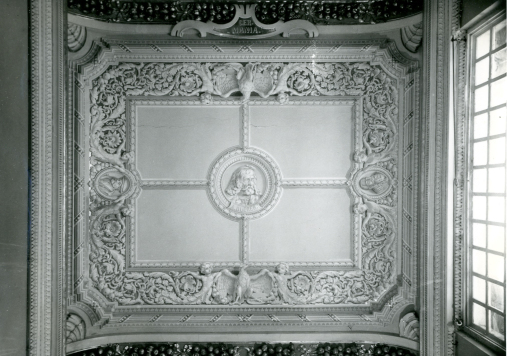

Ceiling painting “Stygian Dream of Psyche”

History of research, conservation, and restoration

Before the beginning of the large-scale post-war renovation of the Palace (in the years 1955-64), a decision was taken to restore the galleries to their Baroque decor from the times of King Jan III. Wherever possible, conservationists revealed the earliest layers of painted decoration on the walls and ceilings. These were in a terrible state, and conservation and reconstruction of the missing architectural, sculptural, and painted elements required a huge effort. In the North Gallery at the time, the pilasters articulating the interiors were recreated and the walls dividing the space from the garden were removed, being closed in with glass walls to protect them from atmospheric factors. In subsequent years, the Garden Galleries were studied and subjected to conservation efforts on many occasions.

The comprehensive conservation efforts conducted in the years 2023-2024 on one of the bays of the North Gallery are a further attempt to restore the decor from the times of King Jan III Sobieski. The wall paintings needed to be first cleaned of dirt, as well as many years worth of touch-ups and overpainting. After these had been removed, not only were the original colours and fragments of the composition which had defied interpretation up until now revealed, but the dramatically poor state of the frescoes was also confirmed. Their surface is pitted with numerous pockmarks resulting from hammer blows. This resulted from the way in which the surface was prepared for the application of new plastering during the repurposing of the garden gallery into a painting gallery in the 19th century. The poor state of the original plaster and painted decorations was also caused by the long-term impact of destructive atmospheric factors. In the years 2023-2024, the decorations on one bay of the North Gallery – including among others three frescoes by Michelangelo Palloni and one by Giuseppe Rossi – underwent essential rescue operations, followed by reinforcement, and then restoration works.

The sculptural and stuccowork decorations have survived with nearly no trace of their coloured layers, and have also lost some elements. Painstaking conservation research was the basis for the implementation of restoration works such as the recreation of the dotted background of a group of putti on the ceiling and the restoration of gilding in this area. On the basis of an analogy to the South Gallery and laboratory studies, it was determined that the group of putti were painted a cold grey colour, (“stone” coloured), and this colour was applied to them.

The colours arranged for the architectural elements on the – a warm yellowish-orange ochre – is also intended to refer back to the times of King Jan III. This colour, altered during aging processes, successive modifications and damage, has survived to a considerable degree in, for example, the pilasters of the South Gallery. It has also been found in tiny fragments of the original plaster concealed under later added layers in the North Gallery. Based on samples and analogy, a colour was achieved resembling that which co-existed with the frescoes by Michelangelo Palloni at the end of the 17th century.

The compositions by Palloni in the North Gallery, created between 1688 and 1692, have only partially survived: the Stygian Sleep of Psyche on the ceiling, Psyche Tormented by the Servants of Venus in the central part of the western wall, and Psyche at the Spring of Styx in the central part of the eastern wall. These wall frescoes have deteriorated as a result of atmospheric conditions in the open galleries and primarily due to transformation of the interior conducted in the 19th century. Today we can only guess what may have been the original composition of the paintings. The ceiling fresco has survived in better condition, although its central part comprising most of the figure of the reclining woman, has been completely lost. Currently, this blank has been filled in with a layer of plain plaster due to the lack of iconographic evidence for the reconstruction of the composition.

Conclusions and summary of recent research and conservation works

- The decorations of the Garden Galleries can be dated in the broadest possible understanding to the years between 1682 and 1692, with the sculptural and plasterwork decoration being completed by ca. 1686, and the frescoes painted after that.

- During conservation works, the oldest layers of colour were discovered; a yellowish-orange ochre, pink tones, and greys imitating stone have been confirmed in ornamental groupings from the same period made by Swiss-Lombard stucco workshops in Central Europe.

- A formal and functional analysis of the architecture of the Garden Galleries in conjunction with their earliest iconographic messaging as well as the need to maintain the cohesive character of the place justify the reconstruction of the colour schemes of both Garden Galleries in tones which reflect the colour scheme of the Palace at the end of the 18th century.

- The bas-reliefs with putti playing out scenes from the story of Amor and Psyche should be understood to be iconographically independent creations of the designer of the stuccowork group.

- The iconographic models for Palloni’s frescoes are unknown. Furthermore, his artistic practices indicate that direct models may not exist, thus meaning that there is no basis from which to recreate the frescoes.

- On the basis of studies by conservationists and in the laboratory, the missing elements of the arrangement of the galleries for which certainty has been achieved have been reconstructed. These are: the gilding in the area of the ceiling, the colour of the reconstruction of the stucco decorations, and elements of the architectural decoration.

All conservation decisions and actions undertaken were preceded by interdisciplinary studies and thorough analyses. The team working at the Gallery under the leadership of Maciej Baran comprised conservationists and other specialists from a variety of fields:

Gustaw Bołdok, Joanna Dziduch, Julita Garwacka, Andrzej Kazberuk, Piotr Kolasiński, Barbara Libera, Natalia Łowczak, Elżbieta Macander, Marta Maciąga, Ida Małolepsza, Ewa Moroz, Katarzyna Pisarska, Iwona Rawska-Brzost, Wojciech Roman, Aleksandra Siebuła, Bogna Skwara, Grzegorz Stępniak, Justyna Szczepańska-Baranowska

Main contractor: MBKZ Maciej Baran Konserwacja Zabytków

Laboratory research: Elżbieta Jeżewska

Supervision on behalf of the Museum of King Jan III’s Palace at Wilanów: Maria Bator-Krupecka

Text: Konrad Morawski and Maria Bator-Krupecka, Elżbieta Grygiel, Anna Kwiatkowska, Agnieszka Pawlak

Works completed in the years 2023-2024 with financing by the Omenaart Foundation.