Giovanni Pietro and Antonio — the Perti brothers in the Commonwealth

Giovanni Pietro and Antonio — the Perti brothers in the Commonwealth - Photo gallery - Element slider

Giovanni Pietro and Antonio — the Perti brothers in the Commonwealth - Photo gallery - Element slider

The Pertis

The family of Perti hails from a small town called Muggio in the valley Valle di Muggio in the Ticino canton in the Italian part of Switzerland. Though no art-historical monograph of the family exists, at least several dozen of its members are recorded to have taken part in architectural and decorative undertakings in today’s Switzerland, Bohemia, Moravia, Austria, Germany, Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, and, of course, Italy, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The earliest known representative of the family was Bartolomeo, the grandfather of the artists from Vilnius and Wilanów discussed below. It is not known whether he engaged in artistic pursuits. The fact that representatives of three subsequent generations of the family did in so many instances, however, seems to suggest that the artistic inclinations of the Pertis may date back to an even earlier time. We know, for instance, of Giovanni Antonio Perti, identified as the builder of the Franciscan church in Český Krumlov, and of Pietro Stefano Perti, involved in raising the palace at Netolice. Also in Bohemia, Carlo Perti worked in Příbram, while Giovanni Battista Perti was employed in Telč. Another pair of Pertis worked in Rome with the famous Francesco Borromini. Another kinsman, Lorenzo Perti (born in 1624 in nearby Rovenna on the Lake Como), operated around Munich, and later, with son Giovanni Niccolo, found employment in the Fürstenfeld monastery and at Neuburg on the Danube, among other locations. Giovanni Niccolo went on to separate from his father and work in several cities of Upper Austria until 1723.

Other than the protagonists of this article — Giovanni Pietro and Antonio — the Commonwealth saw the appearance of several other Pertis at the turn of the eighteenth century, for instance, Filippo (employed by the Dzieduszycki family at Vilkhivtsi), Jacopo and Agostino (working for Jan Stanisław Jabłonowski), as well as Antonio, Filippo, and (perhaps another) Jacopo (at the court of Elżbieta Sieniawska). Sadly, at this stage of research little is known of their activities.

The later generations of Pertis in the Commonwealth have also not been fully identified as yet. One exception is the information from the fortunately surviving archival materials concerning the estate of Giovanni Pietro. The documents indicate that the children and grandchildren of the artist had deeply assimilated in the Commonwealth, blending in with the high society of the wealthy and respected inhabitants of Vilnius. The capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania became home to his sons: Józef and Stefan, supervisors at the Sapieha estate at Antakalnis in Vilnius until 1760, and Jerzy, who married into the Uszacki family; and daughter Franciszka, the wife of the Deputy Cup-Bearer of Pärnu. Among his grandchildren and other kinsmen were also two Trinitarians, one in the Vilnius convent, the other in Trinapolis: Józef of St. Gregory, who died in the Berestechko monastery in 1774, and Jakub of St. Stephen; and Ignacy, who entered the Franciscan order in Vilnius in 1769. A Petri unknown by first name, in turn, owned a brewery in Antakalnis in 1736. The Perti family continued to be active in Russian territories of the Crown until the end of the 1720s.

Interestingly, by the early eighteenth century Pertis in Muggio were no longer land-owners, and the only remaining member of the family served for over a decade as a parson at a poor local parish. With his death, the name Perti disappears from registers. Outside of the Commonwealth, too, the eighteenth century Europe has no known record of the name in art history (outside of the aforementioned, longevous Giovanni Niccolo). This may be seen as a result of the family’s moving to a new fatherland—the lands of the Polish Crown and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

The Pertis lived, worked, and created in the Commonwealth within an Italian-speaking, active, and mobile artistic colony, which included Martino Altomonte, Carlo Putini, Pietro Putini, Giovanni Merli, Giovanni Maria Galli, Giovanni Battista Frediani, Michelangelo Palloni, the Ceronis, the Capponis, and many others. The most well-known member of the family was Giovanni Pietro Perti, who worked mostly in Vilnius. His brother (or cousin) Antonio also gained recognition as an artist and was employed for many years as a decorator in the palace at Wilanów.

The clients of the Pertis

The political elite of the Commonwealth at the turn of the eighteenth century included five distinguished figures who commissioned large-scale stuccoworks. They were: Jan Sobieski, Zygmunt Pac, Benedykt Paweł Sapieha, Rafał Leszczyński, and Stanisław Herakliusz Lubomirski. They maintained tight relations with other significant figures, such as Kazimierz Jan Sapieha, Michał Kazimierz Pac, Jan Stanisław Jabłonowski, Jan Dobrogost Krasiński, and Kazimierz Ludwik Bieliński, all of whom adopted trends promoted by the former five on a massive scale. The projects funded by these immediate followers echoed in undertakings of their protégés, such as the families of Słuszka, Dzieduszycki, Szczuka, Sieniawski, or Kotowski. This group was bound together by familial relations, and often by friendships, as well as participation in the same political factions. Interestingly, almost all of the above bore the title of Hetman, and at least seven developed schemes to attain the Polish crown. These facts suggest that the ownership of a residence richly adorned with stuccoes in modo italico was an important attribute for members of the power elite of the Commonwealth in that period. To obtain these coveted decorations, clients bribed the best artists or employed those who worked for recently deceased patrons, taking over entire groups of workers in the process.

Giovanni Pietro Perti

Giovanni Pietro Perti (listed as Pert, Perty, or Pertij in archival documents, and erroneously as Paretti, Peretti, Pretti in literature) was a stuccoworker referred to as a ‘carver and architectus’ in historical documents. He was born on 16 October 1648 in Muggio, the son of Giovanni Antonio and Caterina. He died in Vilnius in 1714 and was probably buried in Saint Peter and Paul church at Antakalnis. The first mention of Giovanni Pietro’s presence in Vilnius dates back to 28 April 1677 and refers to the laying of the cornerstone for the monastery of Canon Regulars, although it seems very likely that the artist arrived to the Grand Duchy earlier, perhaps as early as 1675. Having engaged (with Giovanni Maria Galli) in preparing stucco decorations for the church of Saint Peter and Paul—commissioned by Michał Kazimierz Pac—he went on to spend the rest of his life at Antakalnis. In 1678–9 the decorations for the main nave were prepared, and until 1681 almost all interior decorations in the temple were ready. Over the winter of 1681–2 the sacristy was decorated.

Archival documents mention Giovanni Pietro Perti on two occasions in 1682. The first is a court case of 20 January, where he served as a witness; the second places him in Pažaislis, where an entry in the liber copulatorum of the local church lists his marriage in the first quarter of the year to one Magdalena Połonowna. This fact testifies to the financial stability of the artist, while his choice of spouse indicates extremely close relationships to other Italians working in the Commonwealth. Despite the Polish-sounding name, Mrs. Perti was in fact the daughter of Michelangelo Palloni, a celebrated painter who worked for the most influential figures in the country, and her marriage ceremony was witnessed by ‘Petrus Putyny and Joannes Galli’. After the marriage, Giovanni Pietro continued to work in the church at Antakalnis as stucco decorations continued to be prepared until 8 November 1684, when, following the death of the founder of the artistic effort, the departing artists received their final payment.

This development inaugurates a break of over two years in archival records, lasting until January 1687, when Giovanni Pietro Perti’s daughter, Katarzyna, was christened in Vilnius (her godparents were Bartłomiej Dawgielewicz and Anna Kowalowa). The fact indicates that the artist’s family has settled for good in Vilnius, and the choice of godparents — local burghers — proves the Pertis’ integration with a circle of friends and acquaintances inside the city. Perti’s artistic exploits over the following two years, up until 1689, are unknown. The years 1684–9 thus constitute a rather prolonged period of absence from the archives in terms of Perti’s work as an artist. Meanwhile, the absence of entries on Perti in registries in the city and in Kazimierz Jan Sapieha’s estates lends credence to hypotheses of the artist’s extended trips outside of Vilnius.

Perti worked for Kazimierz Jan Sapieha since 1689. Together with another native of Ticino, architect Giovanni Battista Frediani, he was employed in the building and decoration of the new Sapieha palace in Antakalnis, completed in the Autumn of 1692. Perti supervised architectural works as well as stuccowork and decorations in the building. He is personally responsible for the artificial stone figures in the main garden gate. Since 1692 Perti was involved in redecorating the chapel of St. Casimir at the Vilnius cathedral. Both undertakings paired him with his father-in-law Michelangelo Palloni, and their fortunately surviving work proves to this day the incredible consistency of their views on art and the mutual influence of the two artists. During the same period, Giovanni Pietro took part in the raising of the Słuszka palace near Antakalnis, where, outside of architectural supervision, he executed decorations, for instance for the surviving tympanum at the main entrance to the palace.

In the latter half of 1692 Perti was in Hrodna, where he and Frediani raised, rebuilt, and decorated a palace for Kazimierz Jan Sapieha. That year saw the erection of an eight-column portico in mixed orders, along with decorative works on the staircase, mantelpieces, and several interiors. Perti can also be associated with stuccoes in the presbytery of the Jesuit church located in close vicinity of the Sapieha palace, founded in the 1690s by Kazimierz Jan Sapieha and Benedykt Sapieha. Under the Sapiehas’ aegis, Perti became the supervisor of the family’s properties in Antakalnis and Šnipiškės, which required of him to take up lodgings in a manor located in the estate of the Artillery Corps of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in Antakalnis.

On 12 April 1694 construction work on the Trinitarian monastery began; the effort clearly involved Perti as a supervisor and decorator (of his works, three groups of holders for escutcheons located over the second-floor windows remain). Two years later, on 26 April 1696, the cornerstone was laid for a monastery church in relation to which Perti was mentioned, though intermittently, at least until 1705.

In 1700 Perti spent a few months in his native Muggio. Despite the decline of the power of his patrons, the Sapiehas, after the battle of Valkininkai (1700), he returned to Vilnius, where he ‘bloodily toiled near the church of Brothers Trinitarians of Antokol’, and also engaged in trade.

Giovanni Pietro’s will, composed in 1705 ‘in poor health, but with memory in good order’, along with the testament of his wife Caterina from 14 years later, have served as the most informative sources on the family of the artist and his economic standing. These documents indicate that Perti continued to be employed by Kazimierz Jan Sapieha in 1700–5 for a yearly pay of ‘two hundred red złotys and a cask of Hungarian wine’.

Both testaments paint the image of the artist as a man in reliable social, marital, and economic situation. They indicate that outside of his artistic exploits, Perti also engaged in trading cloth (he owned a factory in Hrodna worth ca. 10,000 thalers), banking, or rather usury (the amount he had lent in that period exceeds 5,000 thalers), owned two farms in Switzerland and a manor house in Antakalnis, and also leased the Grygieliszki farm. Before his death, Giovanni Pietro organised weddings of two of his daughters: Katarzyna (with a councilman of Vilnius, Jan Hołubowicz, in 1704) and Marianna (with Paweł Ciechowicz, after 1705), which allowed them to enter the patrician circles of Vilnius. His sons — Giuseppe, Stefano, Giorgio — had also assimilated in the Vilnius society.

Crucial to Perti’s professional education was his acquaintance with the artistic circles of his place of origin and its three leading individualities: Agostino Silva of Morbio Inferiore, Gian Pietro Lironi of Vacallo, and Giambattista Barberini of Laino d’Intelvi. Giovanni Pietro’s art was profoundly influenced by several sojourns in Rome, where he observed designs by Roman collaborators and imitators of Gianlorenzo Bernini: Antonio Raggi, Domenico Guidi, and Ercole Ferrata. Without a doubt, Perti was an exquisite sculptor whose sole ventures in this area during his time in the Commonwealth had him work in the least respected of materials — stucco. He also excelled in rearranging existing interiors. A good practical architect, he collaborated as equal with the greatest artists of his era. Palloni, Altomonte, Frediani, and Putini are only a few of the men who knew and valued Giovanni Pietro, a self-conscious participant in the shaping of the Commonwealth’s Baroque at the turn of the eighteenth century. He ranks among the most outstanding followers of Bernini in the so-called second generation of Bernini’s epigones. At the same time, Giovanni Pietro’s oeuvre bears a clear mark of inspiration with the art of Francesco Borromini and the Paris milieu.

Did Giovanni Pietro Perti work at Wilanów?

Setting the life-story of Giovanni Pietro Perti against the chronology of decorative works in Wilanów Palace interiors, one observes an astoundingly curious correlation. The first record of his presence in Vilnius dates back to 1677, although it seems rather likely that he was active in the Grand Duchy since as early as two years before and belonged to a group of Italian artists and craftsmen employed in the construction of the Camaldolese church at Pažaislis. His employment history since the beginning of works on the church of Saint Peter and Paul at Antakalnis in Vilnius is quite well known thanks to surviving factorial books at the convent. At the end of 1684 Perti received the final payment from the local parson and — as the chronicle notes — travelled to his native land. The interiors of the church remained incomplete. The Italian sojourn was prompted by the loss of his main patron and would not have lasted long, since through the seven years spent at Vilnius the artist started a family and set about assimilating in the city. Outside of the information about the christening of his daughter, which took place in Vilnius in 1687, Giovanni Pietro’s actions until 1689 are unknown. Thus, we are dealing with a troubling period of silence in the life of a robustly creative, tested, and independent artist. I suggest that this gap may be bridged with a stay at Wilanów; at least three clues corroborate this hypothesis. The first is the fact that his child was not born in his native land, but in his elected fatherland; this suggests Perti’s deep commitment to the Commonwealth, most likely animated by visions of a better future and career developments. The second clue is the redecoration of the Wilanów residence, executed in 1686 at a dramatic pace by a team of artists markedly different from those who used to work in the palace a few years before. The third — it is highly probable that Giovanni Pietro would choose to come to the aid of his brother Antonio, who was at that time employed at Wilanów.

Antonio Perti’s strong professional standing allowed him to hand-pick his collaborators. His brother was trustworthy and ensured a proper artistic quality. Antonio also knew that Giovanni Pietro was familiar with Roman and Florentine novelties. Sadly, we do not know how the responsibilities were divided, or whether the Pertis employed creative assistants. Perhaps each applied his talents to one of the two royal bedrooms. The stucco decorations on the facets in both interiors clearly belong to a single design, but differ in execution. Stuccoes in the Queen’s Bedroom are more Roman in shape, lighter, the work of a sure hand of an inventive worker. The King’s Bedroom on the other hand is more French in style, marked by graphical patterns, somewhat cooler and more rigid. However, certain details in both rooms suggest that the brothers could trade workplaces or give lessons to some of their assistants, whose manner of forming stuccoes was already taking on individual traits. It is not impossible that they used the same bozzetos, models, graphical projects, and maybe even stucco forms.

Antonio Perti

Antonio Perti was Giovanni Pietro’s presumed elder brother (no direct archival confirmation exists, and unreliable records leave significant room for manoeuvre). He certainly worked at Wilanów in 1703, and three years later found himself in the employ of Vice-Chancellor of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania Stanisław Antoni Szczuka. There is a distinct possibility that he is identical with Antonio Perti, the Margrave of Łubnice, registered in the archives for 1714. Earlier, at the court of Elżbieta Sieniawska, he is mentioned together with Filippo and Jacopo, while an archival detail informing of Carlo Ceroni’s employment in transporting stucco forms from Wilanów to Puławy additionally reinforces the identification of ‘Antonio from Wilanów’ with ‘Antonio in the service of Elżbieta Sieniawska’.

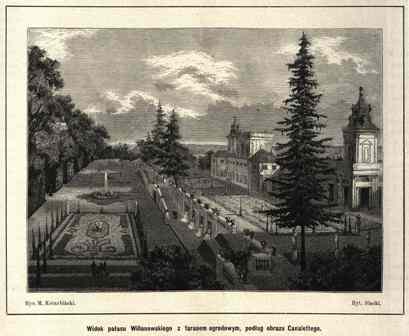

Antonio Perti is also likely the thus far unnamed Perti listed in the register of the royal court in 1696 as ‘stuccoworker of Wilanów’, who had been attending to the King at least since 1681, when the first stucco decorations, described by Agostino Locci in letters to Jan III, were made. During the second phase of stuccoworks — a consequence of the triumph at Vienna in 1683 and the changing positions, aspirations, and political goals of Jan III — the interiors of the major rooms of the main body of the palace were redecorated (the results of the effort have fortunately survived to our times). The artistic quality, condition, and a recent excellent conservation place the fruits of this labour among the most significant sculptural undertakings in Europe.

When the King died, Antonio received his pay and continued to work at Wilanów at least until 1707. Most likely, he also performed some tasks in Sobieski’s estates in the Rus’, perhaps also for the family of Jabłonowski and their milieu. After years of faithful service, he reached the rank of a director of works at the Wilanów estate, settling accounts with the craftsmen and compiling reports for supervisors of the properties of the King’s sons. Sadly, no mention of his presence was found in registries at the Warsaw churches, and the remaining records at Wilanów go back only as far as the 1730s with no mention of the name of Perti. Yet, it is known that, for instance, he maintained close relations with Jerzy Eleuter Szymonowicz Siemiginowski, his neighbour at Wilanów.

Antonio Perti was associated with the Warsaw milieu for about thirty years; his works can be partly identified with the oeuvre of the thus far nameless ‘Master of the Summer Facet’ (i.e. the decoration in the King’s bedroom). Other works in the Wilanów Palace can be ascribed to him, as well. Perti was directly tied to Wilanów, where he hand-picked collaborators for specific tasks. To fulfil royal commissions, he may have enlisted the help of his skilful, diligent, and eminently talented brother from Vilnius, separated from Wilanów by some 500 kilometres.

To sum up, the Pertis played an exceptionally crucial role in the formation of Baroque art in the Commonwealth. Their works adorn Warsaw, Rydzyna, Szczuczyn, Vilnius, Bienica, Hrodna, Lviv, Ol’esko, Zhovkva, Pidkamin’, Ivano-Frankivsk, and likely a spate of other locations. Taking into account that about ten artists bearing that surname are listed as active between 1675 and 1730, it might be said (all things being equal) that we are dealing with a ‘clan’, which, a bit daringly, we might dub the ‘Carlonis of the Commonwealth’. When studies of Pertis’ activities in Austria, Bohemia, and Bavaria extend further, our knowledge of the extent of their impact in the trans-Alpine Europe will expand significantly. This might alter the way we view stucco decorations in the Wilanów Palace. If we factor in the fact that the formidable stuccoworker Baltasare Fontana, who operated in the south of the Commonwealth, and our Pertis were the sons of the same Valle di Muggio, the conclusion might be that artists hailing from that minor region of today’s Switzerland are responsible for lending stucco decorations in the Commonwealth an Italian appearance.

Translation: Antoni Górny