Johann Georg (George) Plersch (ca. 1700–74)

Among eighteenth century Warsaw sculptors active during the reign of both kings of the Saxon dynasty, Johann Georg Plersch clearly stood out as the most famous, creative, and talented sculptor of Late Baroque and Rococo style in the capital. The artist worked for the magnates and the Catholic Church, and, most of all, for both monarchs of the Saxon dynasty. August III honoured him in 1735 with the title of the First Court Sculptor (Der erste Hofbildhauer). Thanks to this title and his position in the court hierarchy, Plersch was able to forge a career unattainable to other chisel artists in Warsaw. The state’s and monarchs’ demand for presentable sculptures was indeed the reason behind Plersch’s arrival to Poland.

The sculptor hailed from one of the Catholic lands of the German Reich, most likely Swabia, where the surname Plersch (alternatively rendered as Blersch) is still more common than in any other German-speaking country. According to an entry in the registry of deaths at the capital’s Holy Cross church, Plersch was roughly 70 years old at the time of his demise on 1 January 1774, but his date of birth might be shifted closer to 1700 given that he arrived in Warsaw in 1722 as a fully formed artist.

The artistic genesis of Johann Georg Plersch’s art remains a subject of speculation based on the formal attributes of his works. It seems that he received basic education in Prague — a major Central European hub for Late Baroque sculpture, digesting the advancements of Italian Baroque art at the turn of the eighteenth century. The oeuvre of two foremost Prague sculptors of the period — Ferdinand Maximilian Brokoff and Matthias Bernard Braun — is notable in that regard. The latter’s highly individual, expressive, somewhat neurotic style, tightly bound to the patterns culled from Bernini and Mannerist sculpture, decidedly affected Plersch’s artistic choices. Mariusz Karpowicz put forward a hypothesis concerning the later education and artistic maturation of the young artist in Rome, one that is hard not to accept. The oeuvre of the Warsaw artist is clearly marked by a ‘whiff of the worldly’, the sheen of the capital of European sculpture Rome was in the early eighteenth century. Plersch’s entire body of work is pervaded by features of Roman sculpture, such as force, spatiality, spectacularity, elegance, a synthesis of studies of nature and antique classical elements, as well as an all-encompassing sensuousness.

It was in Rome that Johann Georg Plersch apprehended the rules of expressive and affective art, one that captures the force of emotions in theatrical action, gesture, and mimicry, a powerful staging of the act and formidable build-up of folding draperies in majestic castings of cloth. His later works invoke mostly the heritage of Gianlorenzo Bernini and his followers, both direct pupils (like Antonio Raggi) and the eighteenth-century masters who adopted his approach (as the sculptors employed since 1718 in decorating the interiors of the basilica of Saint John Lateran — Camillo Rusconi, Pierre-Étienne Monnot, Pierre Le Gros, and Francesco Maratti). However, of sculptors active in Rome in the 1710s and 1720s, the one who affected Plersch the most was Agostino Cornacchini, a Florentine student of Giovanni Battista Foggini. It was he, it seems, that compelled the artist to embrace the rudiments of Rococo. Cornacchini’s art, quite original in the context of contemporary Roman sculpture, woven around such aesthetic categories as the allure of the human frame, sensuousness, and fragility, serves as a conduit between the decline of Baroque and the brief emergence of Rococo in Italy.

The first archival entry testifying to Plersch’s presence in Poland (at Wilanów) dates back only to 1725, but other archival references suggest that the artist may have reached Warsaw in the Summer of 1722, summoned from abroad by one of the royal architects (perhaps Benedict Rénard) to complete certain works at the Royal Castle. For political reasons, the planned resplendent (possibly marble) sculpted decorations of the Senators’ Chamber were eventually never implemented, but the remaining, richly ornamented panelling adorned with panoply motifs in the Deputies’ Chamber can be ascribed to Plersch’s chisel by analogy to his later, individually produced reliefs at the gate to the Wilanów Palace (1728). While working independently on royal commissions, the artist also belonged to the extensive Warsaw workshop (a virtual artistic ‘factory’) of Bartłomiej Michał Bernatowicz, employed mostly by convents in the capital city.

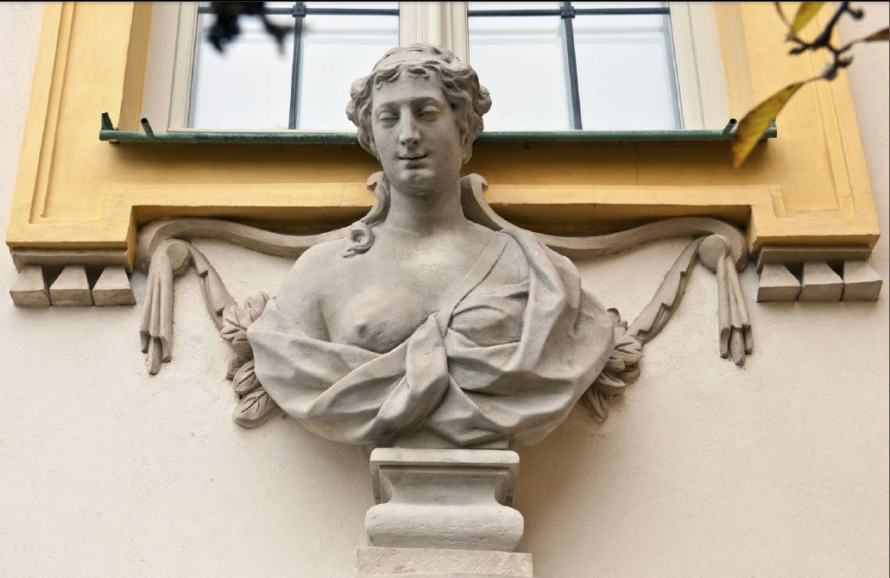

In Autumn 1722 Plersch was employed through Bernatowicz in the interiors of the Piarist church, when architect Giovanni Spazzio enlisted him for the Wilanów palace ‘factory’ of Hetmaness Elżbieta Sieniawska. During the following year he prepared figures of Atlas for the palace towers, and in 1725–6 allegorical and mythological figures and vases for the attics of both wings of the palace (partly in oak), along with female and male busts, placed over the portals of the towers. Plersch worked at Wilanów for Elżbieta Sieniawska and her daughter Maria Zofia Denhoff until 1730. In the meantime, he remained under royal patronage, producing the sculpture of Christ in the sepulchre at Kalwaria Ujazdowska (1728) and sculptural decorations in the Blue Palace (1726). August II also commissioned Plersch to make sculptural decorations in the so-called Lackkabinet at the Wilanów Palace (the King’s Chinese Room); the design for the room came from architect Johann Sigmund Deybel, while the realisation was the work of Plersch in association with lacquerer Martin Schnell.

As an architect for the King and magnates, Deybel was Plersch’s main promoter in that period and ensured further lucrative commissions for the sculptor. Under his aegis and to his designs, Plersch made sculptural decorations — figural and ornamental — for the frontal and garden façades of Jan Fryderyk Sapieha’s palace in Warsaw (1729–33) and ornaments sculptures for the interiors of the courtly church of the Poniatowskis in Wołczyn (1732–3). As he received his nomination as Hofbildhauer, Plersch engaged in an intense cooperation with the main royal architect Carl Friedrich Pöppelmann (1696–1750), son of the renowned Matthäus Daniel Pöppelmann (the creator of the Dresden Zwinger), educated in Vienna, but perfectly acquainted with the latest achievements of French architecture. One of the earliest fruits of this cooperation was a set of figures in the façade of Casimir Palace, which at that time belonged to royal minister Aleksander Józef Sułkowski (ca. 1737–9); today, the figures of Minerva and Hercules at the top of the façade overlooking Vistula remain.

The title of first royal sculptor also assured Plersch of a life-long directorship of all sculptural works in the crown’s construction efforts — which at that time primarily involved extensions in the Royal Castle and the Saxon Axis. The sculpted decorations in sandstone and stucco at the new, monumental eastern wing of the Warsaw castle — designed by Carl Friedrich Pöppelmann under direct supervision of Antonio Solari — was the foremost of those initiatives. The years 1742–52 saw Plersch receive remuneration for this grandest and most costly project executed during his lengthy career. The years saw the creation of the formidable framing for three projections on the Vistula side; the two at either end — with tympanums adorned with ciphers of the king and the queen held by Famas, six acroterions (top ornamentation) in the shape of panoplies, and emblematic and ornamental label moulds — and particularly the main projection (made in 1745–6) with a bombastic cartouche bearing the insignia of the state flanked by panoplies, with female personifications of Poland and Lithuania (which were at the same time personifications of the powers of the Parliament and the King) and of the four continents.

In 1740–50, Carl Friedrich Pöppelmann supervised the final stage of major works on the Saxon Axis according to his own design; for this project, Plersch and associates produced a collection of over 70 allegorical and mythological statues (e.g. a set of figures representing the seasons, sciences and liberal arts, and Roman deities) as well as garden vases. Of this enormous ensemble, nineteen sculptures remain, partly in reconstructions. The production of the décor for the Royal Garden was an immeasurable responsibility as a crucial artistic undertaking, perhaps the most important of all sculptural projects of the time in Warsaw. The choice of Plersch — ‘the first royal sculptor’ — as the director of sculptural works in the royal residence thus must have been an obvious one for the court, maybe even beyond dispute. Plersch’s position as the director of this project was ultimately confirmed after World War II by Jadwiga Kaczmarzyk, who found a signed hand-drawn design representing three garden figures: Flora, Sylene, and Faun, convincingly attached to the sculptural complex at the Saxon Garden in previous studies. At the behest of Carl Friedrich Pöppelmann, Plersch also directed sculptural works in the interiors of the so-called Saxon Chapel at the Royal Castle (ca. 1744–6), producing the main altar with organs and the decoration of the loges (including the royal loge). Here, the sculptor executed the designs of the Saxon artist, while submitting some of his own — for instance, for the side altars, which were eventually rejected. Outside of Warsaw, Plersch also cooperated with Pöppelmann at the so-called New Castle in Hrodna, designed by the latter, where the sculptor produced a splendiferous heraldic cartouche with figural decorations for the garden façade as well as sculptural decoration of the fence adorned with Sphinx with putti and acroters.

The extent of royal commissions sparked an extensive development of the workshop which by the late 1730s became a sort of a royal sculptural ‘company’ including not only the traditional collection of adepts and students, but also fully developed, completely individual sculptors engaged as virtual partners. Archival materials specifically name figures such as Friedrich Krüger, Johann Still, Jakub Wiatrowski, and Franz Anton Vogt as Plersch’s associates. The works of Vogt, in particular, are known in detail. The productions of this sculptural ‘company’ of the King from the latter half of the 1740s also included the equipment of numerous churches, for instance, the collegiate and Augustian churches in Warsaw.

Plersch enjoyed a particularly significant and lasting coopertaion with his brother-in-law (since 1729), the slightly younger Jacopo Fontana (1710–73), an outstanding architect and son of architect Giuseppe, whom Plersch first met while working at Wilanów. Familiar with European novelties (having taken an educational trip across Europe in 1731–3), Jacopo Fontana served as the perfect foil for the sculptor as an artist and protector in the world of magnate and sacred commissions. He introduced a new Rococo spirit of French derivation to Warsaw architecture and sculpture, drawing mostly from the oeuvre of Juste-Aurèle Meissonier — his presumed teacher. The architect provided Plersch with lucrative commissions from several magnates, such as Marshal Franciszek Bieliński (works at the façade and interiors of the palace at Królewska Street, ca. 1744–50; monument to St. John of Nepomuk at the Three Crosses Square, 1752; altar arrangement at the church in Góra Kalwaria, ca. 1760), Voivode of Lublin Jan Tarło (altar of the Holy Cross at the chapel in the Piarist church at Opole Lubelskie, 1744–5; exquisite portal gravestone in the Piarist church in Warsaw, 1751–3, moved after 1832 to the former Jesuit temple), and Jerzy August Mniszech (the picturesque gravestone for his deceased wife, Bihilda née Szembek, at the Reformed church in Warsaw, after 1747).

The cooperation of the two artists flourished particularly through monastic commissions — for the Piarists (a pair of altars at the pillars of the chancel arch at the monastic church in Łowicz, 1744–5; figures adorning the façade of the church in Warsaw — Gracious Virgin, Saint Primus and Saint Felicianus), Discalced Carmelites (main altar at the church in the capital, 1749), missionaries (works at the new façade of the church of the Holy Cross in Warsaw, 1756–60: figures of Saint Peter and Paul in the niches, allegories of Faith and Hope at the portal, angels and cherubs surrounding the cross at the top, and particularly the formidable driveway for carriages with vases and putti personifying the four Evangelists). The sculptural decoration of the façade and interiors of the Visitation church (eight figures adorning the top of the façade, including a group sculpture of the Visitation of St. Elisabeth; interiors with the main altar and the famous boat pulpit from 1760), designed by Jacopo Fontana and executed by Plersch in 1755–60, proved especially spectacular. Plersch went on to cooperate with Fontana again at the Royal Castle in 1762–3, executing carved and sculpted decorations at Deputies’ Chamber, including the uncommon motif of palms supporting the balcony for the audience, and then in 1767 — working already for Stanisław August Poniatowski — at the redecoration of the Marble Room. Plersch’s final major work were the sculptures for the main altar at the collegiate church in Łowicz, designed by Ephraim Schröger, Jacopo Fontana’s student and successor, and executed in 1761–4, including four figures of the Evangelists, angels, the figure of the Apocalyptic Lamb and emblems of sacred power.

Outside of his professional engagements as a sculptor, Plersch also acted as a designer, expert in professional disputes (he adjudicated financial quarrels), and conducted a lucrative business trading in Carrara marble, which — presumably imported on a regular basis from Genoa — he held a constant stock of (it may have been stored at the royal repository of building materials at Solec). The artist also sold his stock of white marble — a highly-valued material in Warsaw — to other sculptors and also directly to founders of artistic undertakings.

Johann Georg Plersch achieved a high social and economic standing. He acted as the godfather or witness to marriages for architects, sculptors, painters, and others on almost thirty separate occasions. Initially, he lived in the New Town, eventually — as a man of means — becoming the owner of two plots of land at Leszno and Królewska Street, where in 1737 he raised a manor ‘partly in stone, partly in wood’. With Magdalena née Fontana, Plersch had seven children, of which Jan Bogumił, the famous painter of the period of late August III and of Stanisław August Poniatowski and an academician in Vienna, achieved the greatest prominence.

Translation: Antoni Górny