The Paradoxes of the Nobility’s Orientalism

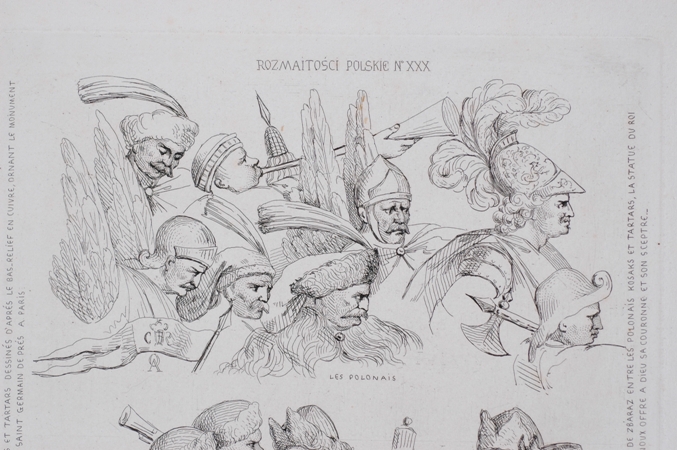

The influence of the Orient in the Old Polish era on various elements of contemporary material culture is very obvious. Despite the Polish hostility, conditioned by political and religious factors, to the Ottoman Empire – because it was the Empire that mainly created our idea of what was oriental – a fondness for horses, harnesses, textiles, weapons or other objects in typical Eastern style could be observed in the culture of the old Commonwealth. In addition, the inclination to luxury, to show off the wealth and ceremonial pomp proved the affinity of preferences. The Polish nobility’s aesthetic taste resembled the Turkish one so much that in Western Europe the Polish and the Turkish male fashions were not easily distinguished from each other. However, such identification would have been considered rather offensive in Poland, as here the Turks were regarded as barbarians. The aesthetic solidarity in question thus appears as a paradox of the nobility’s culture of the 17th century. The conscious fashion for Orientalism as a phenomenon really developed in Poland in the next century, but strangely enough, as a reference to the fascination of the Western aristocratic circles with Eastern culture, the fascination gradually descending to the lower estates of the realm. At this point, it must be added that the Enlightenment Orientalism was inherent and much more multi-faceted (e.g., it included interest in literature and philosophy) than the 17th-century nobility’s Orientalism which was local and, to put it that way, functional.

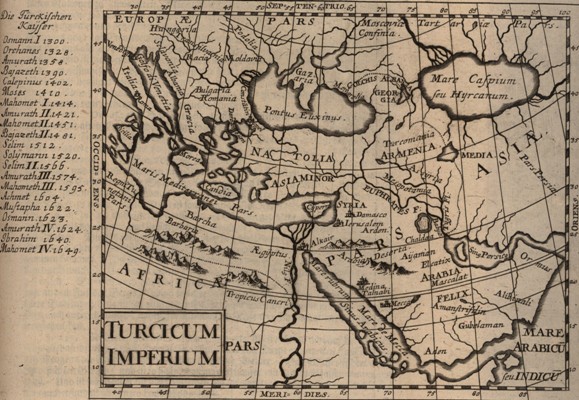

During the period of stronger political tensions between Turkey and the Commonwealth which falls on the time of the reign of the Vasa dynasty as well as, notably, John III Sobieski, the Southern neighbours were regarded as enemies to whom a number of drawbacks were ascribed, whereas the war propaganda of that time revived the myth of Poland as the rampart or a shield of entire Christianity, assigning particular importance to the geopolitical location of the home country. That led among the nobility to the crystallization of the sense of uniqueness or being the chosen nation of God, which is usually referred to, though not quite adequately, as Sarmatian messianism (since messianism presupposes awareness of the sacrifice of life and the necessity of suffering for the sake of a larger community). Such a perspective was conducive to consolidating the negative stereotype of the Turk in the 17th century, although it had been since the Middle Ages that the Muslim countries and their people were portrayed in a bad light. Although some medieval writers were inclined to treat the expansion of Islam as a "whip" with which God punished Christians for their transgressions, the image prevailed of Muslims as antichrists, people of false faith and fierce enemies of Christianity. The "falseness" of religion also implied dubious morality, since in the old days it was faith that legitimized ethical principles (the negative stereotype of the Turk particularly emphasized greed, hypocrisy and lust). Although the religious hostility toward Turks continued to remain alive also later, the emergence in the Renaissance of the nobility democracy in the Commonwealth influenced an increasing emphasis on constitutional differences. The Ottoman State became an example of absolute monarchy, extreme tyranny, in which the subjects are deprived of any civil rights.

Such image of the Orient had predominated in Poland until the Enlightenment and very strongly modelled the perception and presentation of Turkish reality, also by the travellers who visited the Bosphorus (mainly with diplomatic missions). The peregrinators’ accounts are obviously biased, subordinated to preconceived theses for whose confirmation only they sought evidence. Only occasionally opinions resulting from curiosity or even admiration for what the traveller had observed within the hostile country surfaced in the accounts.

For example, Maciej Stryjkowski, in his rhymed autobiography, recalling his stay in Istanbul, when he was forcibly arrested with other members of Andrzej Taranowski’s mission, boasted that when his companions were concerned about their subsistence, he easily found income as an illuminator. He added the following remark to the information:

[...] Because it pays in Turkey

And a lazy nobleman loses his privilege there,

Even if he were a governor’s son. Do whatever told

Drive, dig, plough, or go to the galleys under guard

In these words of the nobleman of limited means, a clear hint can be seen to social injustice prevailing in the country. The Turkish reality is regarded as model.

Samuel Twardowski, in turn, who also travelled to Istanbul in the entourage of diplomat Krzysztof Zbaraski, despite assessing the Ottoman reality quite ruthlessly, heeded with interest an unfamiliar drink and the moral differences resulting from its consumption: "Moreover, those naturalia [natural secretions] from the nose may not be disposed of nor is one allowed to spit. Therefore, the Turks have Kaffa, that is, leaves similar to tobacco or our cow parsnip which, brewed in a covered teapot, they drink as hot as possible, as their lips can bear. Then it acts so that all these naturae faeces extra [natural impurities go out] and communiter [generally] nobody will see a Turk spitting." It is one of the first mentions of coffee in Poland.

In both cases, from behind the then prevailing hostile attitude to the Muslims, the authentic fascination with otherness is visible, which compels to add a plus sign to some elements of the methodically vilified reality.